MEMORIESOFRUSHMERE VILLAGEIN THE 20s & 30sBY DON LEWIS & WALTER TURNER

AUTHOR'S NOTE - Although the Parish of Rushmere St Andrew covers a vast area stretching from the Tuddenham boundary across to Bucklesham Road in one direction, and from the Playford boundary to Leopold Road in the other, the contents of this publication refer to what was generally known as the 'Village' area, extending from the Tuddenham boundary across to Rushmere Heath in one direction, and from the Playford boundary to Humberdoucy Lane in the other.

Published by - Don Lewis and Walter Turner, Rushmere St Andrew, IpswichThe profits from the sale of this publication

will be donated to the Ipswich Hospital Trust.

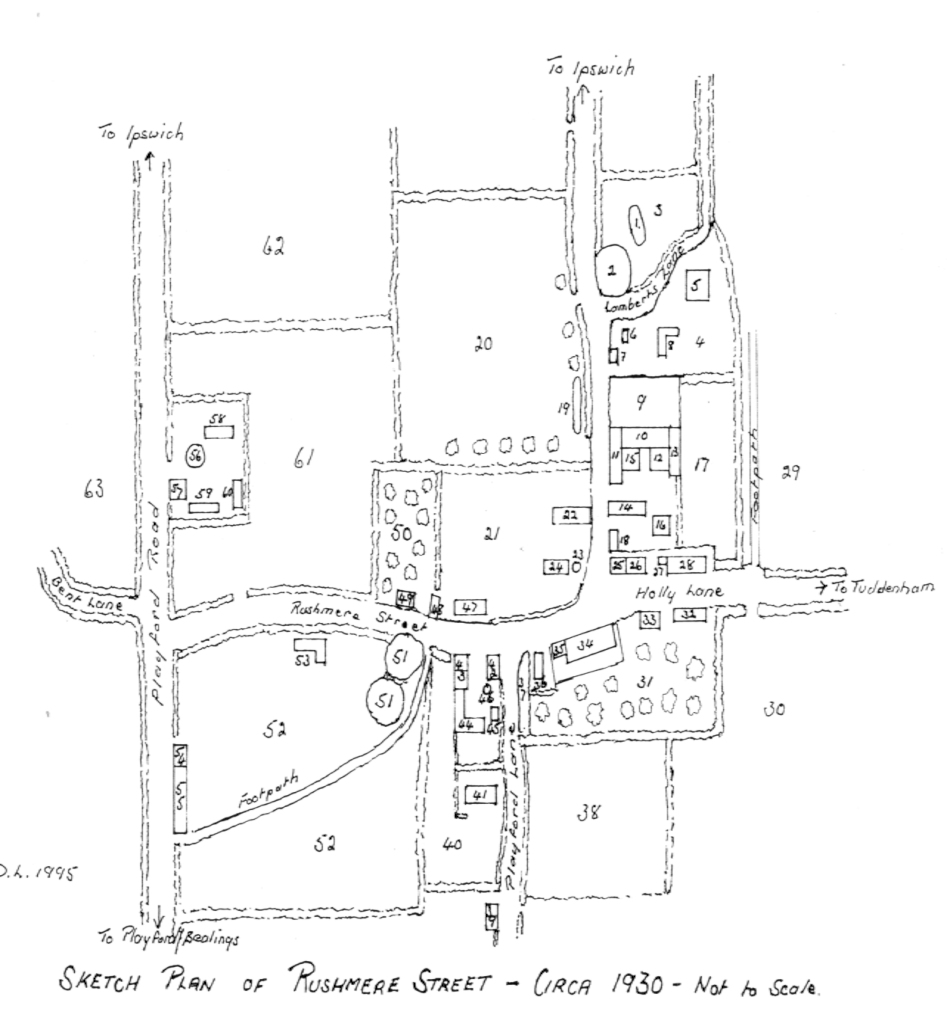

KEY TO SKETCH PLAN

1. Meadow Pond

2. Mellor's Pond

3. Meadow

4. The Limes Gardens

5. The Limes House

6. The Limes Lodge

7. Cottage

8. Fairweather's Dairy

9. Stackyard. Limes Farm

10. Barn

11. Cow-shed

12. Horse-yard

13. Stables

14. Cart-shed

15. Cart-shed

16. Farmhouse

17. Meadow

18. Stone Cottage

19. Muck-heap

20. Field

21. Allotments

22. Cottages (3)

23. Well

24. Cottages (2)

25. Off-licence

26. Cottages

27. Peck's Shoe Repair Shop

28. Cottages (3)

29. Field

30. Field

31. Orchard

32. Cottages (3)

33. Slaughter House

34. Tablet Cottages (5)

35. Welham's Shop

36. Baptist Chapel

37. Private Garden

38. Street Meadow

39. Cottages (2)

40. Allotments

41. Cottages (2)

42. Blacksmith's Cottage

43. Blacksmith's Shop

44. Wheelwrights Shops

45. Stable

46. Well

47. Cottages (2)

48. Cottages (2)

49. Baker's Bungalow

50. Orchard

51. Pokesys Pond

52. Pokesys Field

53. Bullock Shed

54. Falcon Inn

55. Cottages (5)

56. Windmill

57. Cottage

58. Grain Store

59. Store-house

60. Cottage

61. Field

62. Field

63. Field

64. Field

DON LEWIS'S MEMORIES OF RUSHMERE VILLAGE IN THE 20s & 30s

I have known Rushmere village for most of my life, having lived there since 1929 prior to which I spent all my school holidays there when I stayed with my Grandparents. The day following school break-up I would be taken to Rushmere and fetched away again the day before school started back.

At that time Rushmere was indeed a village, with its pretty little dormer-windowed cottages, most of which have now, alas, disappeared. Although only three miles from the centre of Ipswich, it seemed in those days to be at least fifty miles from the nearest town, a completely agricultural area where the wonderful scents of the countryside lingered in the nostrils for many years after it sadly became an urban area. Such is the price of progress. when a country village with all its traditions, natural beauty, its crafts, characters and family connections are lost for ever to be replaced with bricks, mortar and concrete. An area where for hundreds of years the population had lived and worked, usually under primitive conditions compared to modern living, content with their lot, happy in their environment, friendly and happy-go-lucky, wiped out in a few short months under the bull-dozer to satisfy man’s desire to own his own home in this so-called affluent period of our country's history.

But, to return to the narrative of my story, the village as I remember it. Approaching it from Humberdoucy Lane, where the now-closed Post Office stands, the left-hand side of the road, as far as the present Birchwood Drive, appeared very much the same as it does now, although in those days a row of five cottages stood on the site of the present church car-park and a few new buildings have been erected within the grounds of the already existing ones. The pond was there but it wasn't fenced in those days, and horses and cattle stopped to drink as they passed along. On the opposite side there were no houses whatsoever until about 1933 when I can remember the thatched house being built, the first house on the right after passing the church, which was occupied by a Mr Ray, the remaining distance being hedges with tall elm trees interspersed with one or two field gates. Entering the village proper, on the left hand side was Sherwood's farm with stackyard and farm buildings, on the site of the present Birchwood Drive. Then came a collection of cottages and other buildings including the Baptist chapel, general store, off licence, wheelwrights and blacksmith's shops. Behind the chapel was a cherry orchard, and facing it on the right-hand side of the road there were allotments on the site of the present built up area known as "The Willows”. Proceeding towards the present Playford Road, one passed the beginning of Playford Lane and the blacksmith's and wheelwright's shops and then two ponds on the left-hand side, known in those days as Pokesys ponds, the adjoining field being referred to by the same name. In recent years the roadside pond has been filled in and landscaped, the other still remaining where it was. Opposite the ponds was another large orchard, mainly plums and greengages, owned by a Joe Baker. Further along the road on the left stood the bullock shed, still standing today. Apart from this on either side, nothing but trees, hedges and fields, until the early thirties when a number of houses were built on the right-hand side. A hundred or so yards to the left of the junction with Playford Road stood the ‘Falcon Inn’ and a row of cottages. This is one of the few areas of Rushmere which is much the same today as it was then, except that the inn itself has been mainly rebuilt and modernised, as have one or two of the cottages. A short distance along to the right of the junction stood a windmill which in those days ground corn. There were other areas of Rushmere including Hill Farm, but to me they were not part of what I termed the village.

In those seemingly far off days the village was much quieter than it is today. The main traffic passing through being horses and carts and bicycles. There was the very occasional motor vehicle, mainly tradesmen's delivery vans and the 'Swiftsure’ bus which seated about sixteen passengers and ran from Ipswich to Bealings and back twice a day. I remember it as a real boneshaker built on a Model T Ford chassis. It broke down quite frequently, when people waiting for it would end up walking into the town, and probably back again if the repair had not been completed. There was no back-up vehicle to replace it with. The village folk were a very friendly community. Everyone knew everybody else and they were always willing to help each other. Very often someone would be woken up and called out at any hour of the night to attend to somebody who had been taken ill. Housebreaking and other crimes were hardly heard of. People would leave home in the morning and be away all day, leaving either the front or back door wide open in the summertime, or unlocked, though closed, in the winter. Money would be left on the table for the baker or some other tradesman, who would leave the goods, take what was due to him, and leave any change. Most of the menfolk worked on the surrounding farms and would leave home to go to work at 6.00 am, returning at dusk all the year round regardless of season. The women would also work on the fields at certain times of the year helping with haymaking, stooking the corn at harvest time, and potato and pea picking. Sometimes with the local children they would spend all day bird-scaring especially during the fruit ripening season

Pleasures were very few and far between. In their spare time the men would look after an allotment plot where they would grow vegetables and fruit for the family, with perhaps a few flowers to decorate the cottage. The womenfolk seemed to be working from morning till night, washing, cleaning, cooking, bread making, bottling fruit, making jams and pickles, besides making most of the clothes worn by the family. Radio was in its infancy and was only available to the very well off. Evenings would be spent reading or playing games like ‘Ludo’, “Tiddley Winks’ and ‘Snakes and Ladders’. 'Dominoes’, ‘Draughts' and ‘Cribbage’ were also very popular. Occasionally a whist drive would be held in the village hall. Rug making with sacking through which was threaded strips of old cloth was also carried out, likewise needlework and knitting: several households made their own clothes or altered someone's cast-offs to fit a younger member of the family. Many men repaired their own boots and shoes using the kitchen or sometimes even the living room as a cobbler's shop. During the winter months these pastimes would be carried out by the light of an oil lamp, which made it very tiring on the eyes. Most households kept a few chickens in the back yard to provide eggs and the Christmas dinner. Keeping a pig was also quite common. Fed on household scraps it would very quickly be big enough to provide the family with a few months meat.

Sanitation left a lot to be desired, There were certainly no flush toilets and relief was acquired by a trip to the ‘bumby’ which was outside in the yard or at the bottom of the garden. This building, constructed of wood or sometimes brick. and usually festooned inside with cobwebs, normally consisted of a large hole dug in the ground lined with bricks, with a box-like structure of wood with a hole cut in its lid placed over the top. It would be emptied about three times a year, the contents being transported to the nearby allotments where it was dug into the ground. In later years the hole would be filled in and replaced by a bucket which was emptied more frequently. A trip to this building at night in midwinter, with a candle for illumination, was an experience never to be forgotten. It is not surprising that every household boasted one or two chamber pots. The roads which were not made up like they are today, and certainly had no footpaths, were always littered with the droppings of horses, sheep, and cattle which regularly passed through the village. Bathrooms were unheard of. Bath night, usually on Friday or Saturday, consisted of a galvanised bath in front of the living room fire, filled up with buckets of hot water from the copper, a brick structure in the kitchen containing a large copper covered with a wooden lid. and a fire under the copper, which would have been lit purposely for the occasion. Each member of the family would take his or her turn at bathing, the original water being topped up with a fresh bucket as it cooled off. Yet, in spite of all this, there seemed to be far less sickness or disease than we hear of today.

Visits to the doctor appeared to be few and far between although unlike today, if you were feeling poorly you could visit the surgery and know that you were going to be seen on that day, even if you did have to wait your turn. Unlike today when you have to make an appointment for three or four days ahead when by the time you actually see the doctor you are either worse, cured or dead. At the time of which I write doctors were indeed ‘family’ doctors, who visited their patients regularly even without being sent for, and would usually partake of a cup of tea and a piece of cake or a biscuit before leaving. Haw times have changed...

The seasons seemed much more settled than they do today. Winter very rarely went by without sharp frosts and considerable falls of snow. I can remember people skating on the ponds and the snow laid around for weeks, much to the delight of the children but not so much appreciated by the farmworkers whose job was made very difficult, especially where the animals were concerned. The northerly and easterly winds were very strong and extremely cold. Then came Spring with its sunshine and showers. Everyone seemed to brighten up when the bulbs came into bloom. The menfolk began to spend more time on their allotments, preparing for seed sowing while the women concentrated on the spring cleaning. Curtains would be washed to freshen them up after becoming grimy from the dust caused by the coal fires during the winter. Rooms would be cleaned and decorated, the furniture would be polished and the ornaments washed. Everyone began looking forward to the Summer which was nearly always hot, sunny and prolonged. Dust from the roadway, caused by a flock of sheep or horses passing, seemed to get everywhere. In late July, the harvest would start and the rabbits caught on the harvest field would bring a pleasant change to the dinner table. I can still taste those delicious rabbit pies that my mother and grandmother used to make. Some of the more fortunate families would enjoy their annual day trip to Felixstowe which to them was as great an event as a fortnight in Spain is today. Gradually as the weeks went by Autumn would be upon us. The allotment crops would be harvested and brought home to be stored in a frost free place for use throughout the winter. Damp, foggy days could be expected with a definite chill in the air. Firewood would be gathered and cut up ready for supplementing the winter's coal supply, and I could look forward to my annual six months chore of filling and cleaning the oil lamps every day, a job I used to hate doing as [ usually accumulated more paraffin over my hands and clothes than I put in the lamps, resulting in my walking around smelling like a mobile oil refinery,

Christmas in the village was a time I shall always remember. [t was just like the pictures of olden times seen on present day Christmas cards. Nine years out of ten would see snow on Christmas day which provided a very picturesque setting, especially at twilight when the lamps in the cottages were lit. Most people remained indoors on Christmas Day, except for the stockmen who had to go to the farm first thing in the morning and again during the afternoon to attend to the needs of their charges such as feeding and milking. There was an open invitation in most households to anyone who cared to call in for a drink, usually home-made wine, and a mince pie. Christmas was not so commercialised in those days and shops did not start displaying Christmas goods until about three weeks beforehand, rather than in September as is done now. This short spell of publicity in itself added to the magic of the event. Money was not so easy to come by, and presents were much meagre than they are now. Each child would probably receive one or two simple toys with perhaps a few sweets and nuts. The toys would have to be taken care of as we knew that we would not receive any more until the following year. Presents for adults were not exchanged like they are today. Most households could afford to provide a fowl of one sort or another, a pudding, a bottle of port and a box of crackers. The spirit of Christmas meant something and held the family together.

I have tried to paint an overall picture of what life in Rushmere Village was like in the 1920s/30s as I remember it. I have probably omitted a great deal as memory fades with the years. However, I now go on to describe some of the highlights of the village, its annual events, some of its characters, school life, amusing happenings, trades and crafts, all of which played their part in making the village what it was. Although some people might regard such living as primitive and unexciting, they were happy times for those of us who experienced them, and I sometimes think that I would prefer them to today's lifestyle. But time does not stand still and progress must go on, and so like everyone else, I have to accept it.

William Fisk - Undertaker - Wheelwright - Died 1947. - A well-known and respected gentleman who carried out general carpentry work throughout the village He also made coffins and acted as Undertaker, making all the funeral arrangements. On the day of a funeral he could be seen walking to the church in front of the hearse which was drawn by black, plumed horses. He would be dressed much the same as present day funeral attendants are. He happened to be my grandfather and I still have his top hat, which is in pristine condition, in my possession today. He also undertook house painting. mixing all the paints he used himself, from powder, linseed oil and turpentine. Wheelwrighting was another of his skills and I watched him many a time shape and build a wagon wheel from hewn timber using nothing but an adze and hand tools. He did not possess any type of machinery apart from a foot-treadle operated lathe. He also carried out general repairs to horse-drawn carts and wagons and he would make wheelbarrows, hand-carts, garden frames, in fact anything that required a carpenter's skill. He employed two men to help him in his work and they were kept fully occupied. His premises were situated at the corner of Playford Lane and consisted of two workshops, timber sheds, a stable and a saw pit, over which tree trunks would be sawn into planks with a two-handed saw, one man down in the pit, the other on top, He also owned the blacksmith’s shop. which he rented out. His wife, Sarah Fisk, died in 1929 but he lived to the ripe old age of 93, passing away in 1947, until which time he remained active.

Sarah Fisk - Wife of William Fisk - A very busy and hard-working lady always ready to help other people. Would be called out at any time of the day or night to attend to someone who had been taken ill or who had passed away. She would lay out and prepare the body for the coffin. After the coffin had been made she would make the shrouds for lining it. She was caretaker of the parish church for 36 years. She died, probably from overwork, in 1929.

Alfred (Diddley) Dawson - A very stern gentleman who worked the windmill on Playford Road. He also owned and operated steam ploughing engines and threshing tackles, as well as steam rollers, and carried out work on fields and roads throughout East Suffolk. It was a common sight to see a set of tackle travelling through the village. A full set would consist of the engine, pulling a van fitted out with bunks and a cooking stove, in which the crew lived. The van in turn pulled a water-cart. The whole set-up took up quite a length of read, and as it passed the black smoke from the chimney together with the clouds of hissing steam and the smell of burning coal and hot oil was something exciting to see, and never to be forgotten. The mill was demolished sometime in the late 1930s and the steam ploughs were disposed of, the rollers remaining in work well into the 1950s, when the premises were turned into workshops producing agricultural machinery under the direction of the former owner's son, Douglas. The workshops were eventually demolished and houses now stand on the site.

Joseph Crapnell - Known locally as “Blackberry Joe’. The village blacksmith was helped by his son Rufus who carried on the business for many years after his father's death. All types of smith's work was undertaken including horse-shoeing, tool and agricultural machinery repairs, general ironwork, wheel tyreing, in fact anything that came along. The forge was a favourite meeting place for the menfolk, especially during the cold and wet weather, when warmth was to be found in the glow of the fire which burned from morning to evening, occasionally revived by pumping the bellows by a long wooden handle. The ring of the anvil could be heard all over the village serving as an alarm clock for some residents as work started each morning about 7.00 am. Wheel tyreing was interesting both to watch or take part in. The wooden wheel would be clamped down on the platform, which was a flat metal disc let in at ground level, The circumference of the wheel would be measured with a hand-held measuring wheel. The bar of iron selected for the tyre, the width of which depended on the type of wheel, would be cut to length before being put through a hand-operated bending machine which would form it to its circular shape. The ends would then be heated and welded together by hammering to form a solid circle. The tyre would then have holes drilled through it at equal distances for nailing it to the wheel. When this had been done, the tyre would be heated red-hot around the whole of its circumference before being carried outside with tongs to be positioned on the wooden wheel, Two men would then knock the tyre on to the wheel with sledge hammers as quickly as possible before pouring water over it to prevent the wood from burning. When cool the nails would be knocked in and the wheel was ready for putting on its vehicle. Wheel tyreing could be exhausting work and quite a few pints of ale were consumed each time it was carried out. Horses from over a wide area would be brought along for shoeing, and the smell of the smoke created when the new, hot, shoe was embedded to the horses hooves remains in the nostrils always.

Nathan Bye - Shepherd for Norman Everitt. A popular figure, always smiling and friendly, with a very weather beaten face, slouch hat and shepherd's crook and accompanied by two border collie dogs. He lived and slept in a shepherd's caravan during the lambing season and would pass through the village almost daily with his very large flock of sheep.

Welham's Shop - This small shop adjoined one end of Tablet cottages. It was a general store selling almost everything including groceries, hardware, paraffin oil etc. It was managed by Harry Keeble who opened his own shop on Woodbridge Road after the Second World War when Welham's vacated the original shop, which was then taken over by a shoe repairer until it was finally demolished with the cottages.

Peck's Shoe Repair Shop - This was situated in Holly Lane. It was a lock-up shop attached to the end of three cottages.

Limes Farm - The farm was owned by John Sherwood and was situated where Birchwood Drive now is. It was a reasonable sized farm with around ten Suffolk Punch horses and a large herd of cattle. There was a very large barn and stack-yard. A George Smith was head horseman and farm foreman in charge of some ten labourers. The original farmhouse stood adjacent to the farmyard, but was never occupied by the Sherwoods. It was lived in by the Boast family, followed by the Brewsters, who kept and bred Bloodhounds. Local boys earned pocket money for taking the dogs out for exercise.

Harvest time - Muck spreading - Beet slicing, etc.. - Village boys would spend most of their school holidays around the farm helping with the seasonal work as it arose. In the Autumn and Winter they would take the tumbrils of manure to the fields for spreading, prior to ploughing, and the empty tumbrils back to the dunghill for reloading. Likewise, at harvest they would take the empty wagons to the cornfield and bring the loaded wagons back to the stackyard, where the labourers would stack the corn to await threshing in the Autumn. The boys would also fetch beer for the men in stone gallon bottles from the off-licence. At other times they would slice the cattle beet on a hand operated cutter for feeding to the cattle, and help to clean out the stables and the cow shed. Sometimes the labourers would give the boys a few coppers to spend or a drop of beer to drink and occasionally a portion of their ‘elevenses' which usually consisted of bread, cheese and a raw onion. When the hay or corn was being cut the boys would spend all day in the field chasing and catching rabbits which were hidden away out of sight of the foreman, otherwise he would claim them for himself or the farmer. They were recovered at night after all the workmen had left the field.

Fairweather's Dairy - This was situated adjacent to the stackyard attached to the cottage in which Mr Fairweather, the dairyman, lived. The cottage is still standing and is occupied today. Milk from the farm was brought here for disposal. In the dairy and nettice (cool room) there were large shallow pans into which the milk was poured. Some of it would have the cream skimmed off while some would be made into butter and cheese. The rest would be sold as fresh milk. Local children would be sent to the dairy each day to purchase the milk which was brought home in a variety of containers such as screw-top beer bottles, jugs or tin milk cans fitted with a lid.

The Limes - This was a large house which stood in its own grounds on the corner of Lamberts Lane and was occupied by Major and Mrs Mellor. The Major was looked upon as the self-appointed village squire. They employed a housekeeper and several servants including gardeners and a coachman. They would ride around the area in their horse-drawn carriage and as they passed, men and boys were expected to doff their caps and the girls and women had to curtsey. At Christmas time Mrs Mellor would ride round the village and give a 1/4lb tea to each household. On leaving school, my brother went to work at The Limes as a ‘Backhouse’ boy whose job it was to do a variety of chores both in the kitchen and garden. Every morning he had to clean and polish several pairs of riding boots and shoes. On asking for a new tin of shoe polish after some two months polishing, he was told by the lady of the house that “what he needed was a little less polish and a bit more elbow grease. He had to work six and a half days a week, Sunday afternoon off. Once when invited to attend a wedding, he asked for Saturday afternoon off and was promptly told, again by Mrs Mellor, that she wasn't aware that the working classes were entitled to a half day holiday. However, he took the afternoon off and was stopped sixpence (2.5p} from his wages which were at that time 6/- & week (30p in todays money).

The Cottage - (Chevalier) - This was situated a little further along the road towards the church, and in fact it is still there. It was occupied by a Mr and Mrs Chevalier. They were a very likeable couple, and treated everyone with respect regardless of their station, and were always ready to help anyone in trouble. Mr Chevalier was one of the early wireless pioneers, and had some very weird looking equipment in his house. I can remember particularly some very large glass valves, almost as big as footballs, and a large array of big tuning knobs and switches. He would obtain the help of anyone who was passing to assist him in positioning a new aerial. One end of the wire would be affixed to the house, the other end to a pole which the unfortunate person would have to carry around the garden, holding it upright until the strongest signal was received. A local girl by the name of Lizzie left school and was taken on by the Housekeeper as a kitchen maid. One day she was ordered to skin a rabbit and prepare it for cooking. Instead of skinning it, she ‘plucked’ it by pulling off ail the fur. Needless to say, she was never given the same job again.

Post Office - This was the front room of one of a row of cottages which stood in front of the Post Office that recently closed. It was run by a Mr Ashley. As one opened the door a very large bell on a spring would clang away. There was a step down into the shop which could be quite a hazard for anyone who didn't know about it as the floor was at least nine inches lower than the step. Mr Ashley used to sell a few different kinds of sweets which were stored in glass jars on shelves around the walls which necessitated the use of steps to reach some of them. Mr Ashley was a very short man and the children would take advantage of this. After school three or four of us would go into the shop together. The first one would ask for a halfpenny worth of aniseed balls. He would climb the steps, take the jar down, weigh up the sweets, close the jar. climb up and replace it on the shelf, The second one would ask for a halfpenny worth of aniseed balls, and the climbing process would be repeated, then the third one and the fourth and so on. Each time he carried out the climbing. He never did catch on and leave the jar down until we had all been served. At least he got the exercise.

The Village School - Situated in Humberdoucy Lane - (now much enlarged and a centre for the disabled) — consisted of two large rooms. one slightly smaller than the other. The smaller one was used by the infants, the larger one catering for two classes divided by a curtain suspended on an iron rod. Each class could always hear what the other one was doing, making it very difficult to concentrate on anything. The curtain would be drawn open first thing every morning so that both classes could take part in hymn singing and prayers, after which the curtain would be drawn again to divide the classes and lessons would begin. I only spent two years at the school, moving from Ipswich to Rushmere in 1929 and progressing to the newly built Kesgrave Modern School on its opening day in 1931, when I was 11 years old. There were three teachers (all spinsters with the ferocity of lions) at Rushmere when I first attended. Miss Salter was the Head mistress and taught the 11-14 year olds. She ruled with a rod of iron and was an expert in wielding the cane for the slightest misdemeanour: even the girls were not spared the pain it inflicted. Miss Stannard taught the 8-11 year olds. She excelled in giving a clip of the ear to any unsuspecting child. A Miss Werts taught the infants. They ranged between the ages of 5-8 years old. Her favourite punishment was to rap the offender’s knuckles with the knob shaped end of an easel peg. I might say that it was not at all pleasant to experience. All three classes were mixed, both boys and girls together. Each teacher always remained with their own class, teaching every subject in the so-called curriculum of the time. Most of the week was spent in the class room; games and sport were not thought of in those days, although we partook in what was known as ‘drill’ for about a half an hour each week providing it wasn't raining.

After prayers, the first lesson every morning would be arithmetic, or sums as they were generally known. The teacher would explain, with the help of the blackboard, how certain calculations should be carried out in order to arrive at the correct answer. Then ten sums would be set which we had to work out while the teacher sat and looked at the day’s newspaper. After about half an hour, the teacher would come round the class checking the answers. Those that were wrong would have to be done again: this carried an until all pupils had got the ten sums right, Once a few red ticks had been received, little slips of paper containing the correct answers would be discreetly passed around the class for the benefit of the not-so-bright pupils. This helped to speed up the lesson, as. once everyone had received ten red ticks the class progressed to the next subject. possibly reading, composition writing, history or geography. Behind the school was an area of ground divided into small plots, each about 12' x 8'. Each senior boy was allocated a plot on which he grew vegetables and flowers. A Mr Payne would attend two or three afternoons a week to teach the boys the rudiments of gardening, possibly because it was thought that country boys automatically became horticulturists when they left school and started working. The senior girls would be instructed in sewing, knitting and general housework. At that time most girls on leaving school ‘went into service’ as it was known, becoming scullery maids and housemaids to the better off. Many devilish but generally harmless pranks were carried out. Sometimes the culprit was singled out and received punishment, either standing in the corner, writing lines, staying in or the dreaded cane. Despite this the days spent there were happy ones. There were no school outings as there are now. Every year on Empire Day, providing the weather was dry. we would be marched to the meadow higher up the road where we would spend the afternoon making daisy chains. School holidays were much shorter and less numerous than nowadays.

The caretaker, a Mr Webb, lived in the school house which was an integral part of the building. He had a wooden leg, the result of a Great War wounding, and we used to refer to him as ‘stumpy'. During the winter months his wife made cocoa at lunch times. Each child received a daily mug full for which we had to pay 1d per week.

The Village Hall - Men's Club - The original Village Hall, situated next door to the school was, I believe, an ex-army hut from the Great War. I think it was donated to the village by Major Norman Everitt, a local farmer, for use by the local lads returning from the forces. It was used in the evenings by the Men’s Club. They would meet there to play billiards, cards etc. Around 1930 an additional room was built at the rear end of the hall specifically as a billiard room when an additional table was purchased. From then on the main hall came into more general use by other organizations such as the scouts, guides, women's institute etc. Dances (village hops) were held regularly on Saturday evenings when the younger people of the area would vie with each other for partners.

Jumble sales were held regularly throughout the year and around Christmas time the annual ‘Concert’ would attract a full house at sixpence (2.5p) a time, half price for children. Most of the stars of the show were local people and although not exactly of ‘Palladium’ quality, everyone enjoyed themselves. After the final curtain, the long walk home in pitch blackness. There were very few cars and no street lights in those days. Most buildings were still lit by oil lamps. The old hall remained until very recently when it was replaced with the new Community Centre.

The Parish Church - At the time to which I am referring the church was much smaller than it is now; it was probably as it was originally built, small and welcoming with beautiful stained-glass windows and choir stalls. The lectern took the form of a brass eagle. Unfortunately this seemed to disappear when the extensions were carried out in more recent years. I must admit, I don't think it improved the church one little bit when it was supposedly modernised. I can remember going there as a boy with my grandmother when it was still lit by oil lamps which tended to cast deep shadows, creating a feeling of wonderment. The pew-ends were decorated with carved figures. certain pews being reserved for the so-called gentry. At that time the organ was situated behind the left-hand choir stall as you looked towards the altar. The organist, a Mr Ashford, who was totally blind, lived on Woodbridge Road at the corner of St Helens Church Lane. Every Sunday he would walk, on his own, to and fro twice. for morning and evening service, and also during the week for funerals, weddings etc. The churchyard always seemed a fascinating place with its large gravestones and tomb-like structures. In those days glass-domed artificial wreaths with metal bases were very much in vogue. On the way home from school we would go into the churchyard and lift these domes slightly as they were a favourite hiding place for grass snakes.

Once I was asked if I would blow the organ as the regular organ blower was sick. To carry out this task you were enclosed in a little room behind the organ and it was blown up by pumping air into the bellows with a wooden handle affixed to the wall. A small lead weight on a string would, by moving up and down, indicate when more wind was required in order for the organ to play. Unfortunately on this particular day I fell asleep during the sermon and all the organist got when he wanted to play the next hymn was an unusual creaking sound. I was never asked to stand in for the organ blower again.

Miss Talbot ~ Church cottages - On the site of the present church car park stood a row of five cottages. They had no front gardens, the front doors opening up onto the road. In one of these cottages lived an eccentric spinster by the name of Talbot who thought the world was infested by evil spirits. When she needed water, she would lower the pail into the well, but, she would always ask a neighbour, usually a Mr Foulger, to pull it up as she was certain that evil spirits would be brought up in the pail. At night she would stand at her open front door ringing a small hand-bell to frighten them away. Naturally, she was a regular target for the children who would scratch on her front door or rattle the door knob, and then run away when she opened the door, ringing her bell.

The Annual Village Fete & Flower Show - This annual event was the highlight of the year and was always looked forward to with great anticipation and excitement. It was held on the church meadow in July and attracted people from a wide area. Marquees would be erected for housing the vegetable and flower shows and for the serving of refreshments. There was also a roundabout and swings for the children. A brass band would play throughout the afternoon and later in the evening dancing would take place on an area where the grass had purposely been cut shorter. Various stalls and sideshows would be set up around the perimeter, coconut shy, hoop-la etc., one of the most popular being bowling for a pig, the winner being presented with a piglet which would be taken home to fatten up for the table. Another area of the meadow would be marked out for races, flat racing, sack race, egg and spoon etc. also high jumping and long jumping were carried out. Anyone could enter and there were classes for men, women and children. Cash prizes would be awarded to the winners. The flower and vegetable show was always well supported, both by the exhibitors and the public alike. Parishioners would bring along their produce to compete against each other. Lots of care and attention would be given to staging and quite a lot of, sometimes hostile, discussion would ensue after the judging had taken place. The flower tent was usually a joy to behold and was always well patronised by the ladies who would hover around at closing time hoping to be given a bunch of roses, sweet peas or some other variety that the exhibitors had no further use for. Unfortunately, for some reason unknown to me, the annual fete fizzled out some time midway through the thirties and was sadly missed by many.

Rushmere Heath - The heath has been used as a golf course for as long as I can remember and has changed very little over the years. To us boys it was somewhere to go when we we were not doing anything else. Many’s the time we were told off by an irate golfer because he thought we had strayed from the footpath and that we shouldn't have been on the heath at all, despite the fact that it was common land and we were all sons of commoners. Admittedly the greens and fairways were leased to the golf club, but, they couldn't stop the parishioners or anyone else for that matter from being there providing no damage was done to their playing areas. On the other hand, some players were glad of us to dredge the valley pond for lost halls so that they could purchase any we recovered from us for next to nothing. We would make a shallow-type basket from small mesh wire-netting about two foot long at the front end which was weighted with a flat bar of iron. To this would be attached a length of thin rope which was longer than the diameter of the pond. The basket, or dredge as it was sometimes called, would be laid at the edge of the pond. We would then walk round the pond letting out the rope until we arrived at the opposite side, when the rope would be pulled in, dragging the basket across the bottom of the pond. hoping all the while that it would have scooped up a ball or two on the way. Sometimes a whole day would be spent doing this and not a single ball would be recovered. A few village people would cut whins on the heath to bring home for heating the brick ovens which were used for baking home-made bread. Others would cut a few turves on occasion, perhaps for turfing the grave of a loved one in the churchyard. Incidentally, the heath fires of recent years are not something new or unusual. There have been fire outbreaks on the heath for as long as my memory serves me. An annual occurrence used to be the paying out of what was known as the ‘heath money’ which dates back for many years, when each householder received a sum of money. A tablet explaining the conditions was originally fixed to a row of cottages which are long demolished. It is now affixed to the front of the Baptist Chapel and makes interesting reading. This money is no longer paid owing to the huge increase in the number of households in the parish, which has reduced the amount payable to such a minimum as to make it no longer worth while.

The Arm of the Law - There have been a number of policemen stationed in Rushmere over the years. For many years we had our own officer who lived in the police station house on Weodbridge Road opposite the golf course. Some were very good and sociable, others were not so good, In my boyhood we had an officer stationed here by the name of Pearl. Actually he was not a bad old boy being jovial and talkative, although rather slow in his movements, but, for all that he did a good job at keeping the peace and although us boys would speak to him we always had a certain fear of him. In those days all the men and boys wore a head-dress of some description, usually a flat cap with a peak. I can remember one particular day when two or three of us had been down Holly Lane collecting bird’s eggs which was a popular pastime at that period. Any egg that we had taken from the nest would be placed inside the front of the cap for transportation home when a hole would be made in each end of the egg with a pin so that the contents could be blown out. Obviously you had to make sure that any egg taken was fresh so egg collecting was a daily task. However, on this particular day to which I refer, as we approached the village street someone said “Look, there's old policeman Pearl". He was standing outside the chapel, and as it was quite obvious that he had seen us we decided to carry on walking rather than attempt to scarper. He stopped us. "And where have you boys been” he said. "We've been for a walk down the lane” was the reply, "You haven't been touching the birds nests have you". "No Mr Pearl, we only looked at some but we did not touch them". "So you haven't taken any eggs” said he. "Oh no Mr Pearl", whereupon he pressed his hand firmly on the front of my cap saying "You are a good boy aren't you". Gradually egg yolk and whites began to seep from my cap and down my forehead. That was enough to put us off bird nesting for the rest of that season. On another occasion, we were scrumping apples from a tree which overhung the surrounding wall of ‘The Limes’ One boy had been lifted up so that from the top of the wall he could climb into the tree, pick the apples and drop them down to us. Suddenly Mr Pearl came in sight so those of us on the ground beat a hasty retreat leaving our mate up the tree. “I think you had better come down" said the copper. "Not while you're there" was the reply". “Ah well, I've got plenty of time, I'll sit down here and have a smoke and wait till you're ready to come down" said Mr Pearl, filling his pipe and lighting it. After about an hour the hostage had had enough and decided to come down, when he received a mighty clip round the ear and was told not to get caught again. Policemen would inflict punishment on the spot in those days and it usually worked wonders.

Tradesmen's deliveries - Supplies would be brought into the village by various tradesmen, usually by horse and cart, and normally once a week. Barnards would bring small bundles of hay and straw. chicken and pig food and flour which was ground in their own mill on Woodbridge Road. The Co-op oilman was another weekly caller selling paraffin oil from a large tank mounted on a horse drawn cart. He usually carried soaps, washing powder, disinfectant. candles etc. as well. Likewise the Co-op baker and milkman made daily deliveries of bread and milk. They also made weekly deliveries of the grocery order. In those days the Co-op had dozens of horses delivering goods to the whole of Ipswich and the surrounding villages. Manthorpe’s made weekly deliveries of coal, selling it off the cart. Most people bought just one hundredweight each time he called. On Monday evenings Becket's of Westerfield, two brothers, would call, This was my very first experience of the truly mobile shop. He drove a Model T Ford van which contained a vast range of goods, mainly groceries and paraffin oil which was drawn from a tank suspended beneath the body of the vehicle. Another firm, the name of which escapes me, used to come round selling non-alcoholic drinks such as ‘dandelion and burdock’, ‘stone-ginger beer’, ‘cloudy lemonade’ etc. in one gallon stone bottles which cost about one shilling (5p) a bottle. ‘Corona’ also made weekly deliveries of mineral waters, four quart battles in a wooden crate which also cost a shilling. During the summer months the ‘Creamax' ice cream man would arrive on two evenings each week on a motor bike fitted with a box type side-car. He came from somewhere in Norfolk and usually did a good trade.

The dawn of progress - As far as the village was concerned, the 1930s heralded the commencement of luxury living. Electricity, with its overhead cables, was laid on around 1932. This was quickly followed by gas supplies. Not all dwellings were automatically connected to these services and some householders continued to use oil for cooking and lighting. It depended entirely on whether the people who owned their dwelling could afford to pay for having them installed, or in the case of rented property, on whether the landlord was willing to meet the expense. Some people preferred electricity while others preferred gas for cooking and lighting and a few were lucky enough to have both, gas for cooking and electric for lighting. The water main was laid around 1936 as far as I remember, and the water in the two wells which had supplied the villagers for so many years was condemned by the authorities as being unfit for human consumption, much to the disgust of the residents who took an instant dislike to the taste and hardness of piped water. Not all dwellings were individually connected and some people had to share a communal tap installed outside in the yard. The two wells were filled in by householders who found them convenient for the disposal of unwanted rubbish. Sewerage did not arrive until after the Second World War, until which time, as mentioned earlier. night soil and slops etc. were dug into the garden. The weekly collection of household rubbish started in the 1950s, prior to which kitchen waste was rotted down for compost, the remainder being burnt on bonfires. Bottles, tins, etc.. were periodically buried in the garden in holes dug especially for the purpose.

The Gyrotiller - Casting my mind back to sometime in the early thirties I can remember the "Gyrotiller" coming to Rushmere on what I think was an experimental tour. It was a massive diesel driven machine of what appeared to be massive length and height. On the back of it were three large rotary tillers which turned and broke up the soil to a depth of two feet or more. It was fitted with large lamps on front and rear and it carried on working throughout the night. It apparently was not very successful and very little more was heard of it.

The Harvest Festival - There were always two Harvest Festivals in the village, one at the Parish Church, the other at the Baptist Chapel and as they were held on different Sundays both buildings were always full. The inside of the building would be decorated with flowers, fruit, vegetables, sheaves of corn and always the harvest loaf, a very large loaf of bread, especially baked for the occasion. Every corner, shelf and crevice would contain something that had been donated by the parishioners. The singing of the harvest hymns created a wonderful atmosphere which remained in the memory for a long time. On the Monday, all the produce would be taken to the hospital or children's home.

The Public Houses - As now, there were always two public houses in the village area, I have already mentioned the ‘Falcon’ elsewhere. The second pub, in Humberdoucy Lane, now known as the ‘Garland’, was originally called the ‘Greyhound’, It used to be completely different then from what it is now. In the days of which I speak it was not much more than an over-large cottage with a very small bar and a smoke-room lit by oil lamps, in fact it was very like something out of a Dickens novel. On the corner of Holly Lane was the ‘Off-Licence’ which was also well patronised and rarely short of customers.

It is on this note that I end my story of Rushmere Village as I remember it. It was with some trepidation that I began writing these notes, and it might never have come about, but for the urging by my son, who felt that the life of the past should be recorded for the benefit of future generations. I am glad now that I decided to do it and it is with great pleasure and appreciation that I now hand over to Walter Turner, a lifelong friend, who has assisted me in making the story complete.

WALTER TURNER'S MEMORIES OF RUSHMERE VILLAGE IN THE 20s & 30s

Street Farm (Limes Farm) - On the site of the present Birchwood Drive

The farm was owned by Mr John Sherwood and covered about 150 acres, consisting of three dairies with about thirty cows in each, eight horses of which seven were Suffolks and a pony with a cart which was used as a runabout. Eight or nine men were employed to work the farm. As a boy, one of the highlights, apart from riding in the wagons at harvest time was when the threshing tackle moved in during the winter months when we would turn up with our sticks and cudgels to catch the mice and rats that would run out of the bottom of the stacks.

There was another small dairy further along the road. run by a Mr Fairweather who kept two cows. Each day we would be sent to the nettice (cool room) with our jugs and cans to collect the daily milk supply. Near by was the big house owned by a Mrs Mellor after whom the pond at the corner of Lambert's Lane was named. She also owned the adjoining meadow and was Mr Fairweather's employer. Every Christmas time Mrs Mellor would give each household in the village a quarter pound of tea.

Holly Hill (Now called Holly Lane)

I was brought up at No 5 by my grandparents, my mother having suffered a broken marriage which meant that she had to go into service in order to help the family budget. My granny used to run a small shop, before my time, at this address, a little general store which was actually the first shop in the village. She gave it up later when a larger one was opened next door to the chapel, My grandfather used to sit outside on a chair during the summer and do a roaring trade with oranges as people passed by for walks down the lane on a Sunday afternoon. I think he sold them at 5 for a penny.

On the opposite side of the lane, where some of the Holly Lane bungalows now stand, was an orchard looked after by a Mr Teddy Baker. In this orchard were three cherry trees behind some greengage trees. Starlings are very partial to cherries and I well remember standing next to my grandfather one day, when suddenly there was a commotion in the cherry trees. My grandfather said "here boy, chuck a brick into that cherry tree and scare those beggars off” which I did. Next minute there was a terrific shout and a swear word or two - poor old Teddy was up in the tree gathering cherries.

At No 6 was a small shop owned by a shimmaker (shoe repairer) who was known as Jack Peck the cobbler. He lived in Milton Street in Ipswich and travelled to Rushmere about three times a week to repair the villagers' shoes. He liked his liquor and he had a tabby cat which would drink beer out of a saucer. Further along the lane on the opposite side there was a slaughter house owned by a Mr Joe Baker who also owned the ‘Street meadow' on which the first batch of council houses were built in 1952-4. He employed two men, Nearly everyone in the village at that time kept a pig or two which eventually ended their lives at Baker's slaughter house where us boys would hang around on killing day to get the bladders which were blown up to use as footballs.

To return to my grandparents. They were retired when I was a boy and each received ten shillings (50p) a week state pension which was known as Lloyd George's payout. The rent of the cottages, which were owned by Joe Baker, was one shilling and a farthing per week, just over five pence in today's money. People were quite hard up in those days and my folks were no exception. Granny used to take in sewing and other various jobs in order to make a few coppers. I well remember one Christmas time when on my arrival home from school, the backhouse, it could hardly be called a kitchen, was deep in feathers with plucked chickens lying in every available space. The poor old folks had been busy all day making a few pence to buy a present or two for my stocking.

At the end of the lane opposite No 1, which was an off-licence, was a well from which we had to draw water. Monday was always recognised as washing day when the well would be in full-time use. All water had to be drawn from the well, there being no taps in those days.

One day I was sent to the well to fetch two pails of water. Having attached the first pail to the chain I started lowering it into the well, which was about 80 foot deep, by turning the handle backwards. Thinking that it would take ages to lower the pail to that depth I decided to do what I had seen the men do many times to speed up the process which was to release the handle and ease it down by pressing the palms of both hands round the roller to act as a brake. Unfortunately it didn’t work for me. There was a tremendous crash as the pail hit the water. Immediately, I found myself being told off by a Mr Vic Naunton, whose ornaments bad fallen off his mantlepiece from the vibrations. The wall of his cottage was barely two feet from the well. On top of this I had lost my pail and I had to get a man with a set of creepers (grappling hooks on a rope) to try and hook my pail out. Needless to say, my visits to the well were curtailed for a while.

There were several trees in Holly Hill at that time and practically every afternoon the women would go wooding, gathering wood for the fire to supplement the coal which was very expensive. Us kids loved dragging home whole branches which were then cut up into logs. In the late summer and autumn the same women would go blackberry and sloe picking. The favourite spot for this was known as the 'Warren’, an area situated to the north of the river Finn. Most of the fruit collected would be used for making wine and jam. Dandelion blooms were also favoured for wine making. My grandparents used to make lots of wine of all sorts, which was placed in the scullery to ‘work’ after being bottled. It was nothing unusual whilst having a meal to hear a bang from the scullery as a cork was blown from a bottle and very often the cork would be embedded in the ceiling, such was the force at which it discharged itself. I can remember one very cold day when the insurance man called to collect the weekly premiums. He looked really perished with running eyes and a very red nose. My grandfather asked him if he would like a glass of wine to help warm himself up. "Yes please” he said. So he had one. “Good stuff" says he. "Like another one?”, "Oh yes please". I don't remember how many he actually had. but, I do remember that on leaving he fell off his bicycle three times in about thirty yards.

I can remember that occasionally a lady 'tramp” (vagrant) known as Mother Mackenzie would visit the village when she would set up a stall in Holly Lane. The children always went to see her and would help her sort out her belongings, which she pushed around in an old broken down pram. Another tramp which visited the village fairly frequently was Darkie. a rough looking old chap, but like Mother Mackenzie, if treated with a little respect they were both quite harmless.

During the winter when we normally had heavy snow we would recover our sledges from the shed where they had been stored for the summer and proceed to the bottom end of Holly Lane to what was known as the ‘Grove’, actually a meadow on the side of a very steep hill. We spent many happy hours there sledging down the hill. That was the easy part, the hardest part was trying to gain a foothold to climb to the top again. However, apart from a few bruises we never did have any serious accidents or injuries. During the summer months the local scout troop would occasionally set up camp on the top of the hill. There was a small sandpit next door which was used as a rifle range by the local Home Guard during World War Two.

Rushmere Flying Field

What are now Willis Coroon's and Crane's sports fields were at the time to which I relate arable fields, In the early 1930s, Alan Cobham (later Sir) the aviator, who was quite famous at that time was touring the country offering flights at around £5.00 a time to all and sundry. One of his stopping off points happened to be one of these fields. Naturally, many people went along to see him and quite a few of the locals paid their money and went up. I would have loved to have gone up, but, being still a schoolboy there was no way that I could afford it. However, Rushmere can include a flying field in its history even if it was only for one day.

Farms, Fields and Ponds

There used to be several farms around the village area. Starting at the heath end of Humberdoucy Lane there was Mr Pipe’s “Heath Farm” of roughly sixty acres including a small meadow and a pond which in wet weather would overflow across the road. Much of this land today is taken up by sports fields and includes part of St Alban’s School field. Proceeding along Humberdoucy Lane, crossing Rushmere Road, there was “Rushmere Hall Farm” on the left hand side, just past the present Community Centre. It was owned by a Mr Benjamin (Lenny) King and was quite a large farm stretching from the Lane to Colchester Road, the site of the present Rushmere Hall Estate. There was a large pond in the farm yard on which was a rowing boat that the family would use for pleasure. Further along the lane was another pond known as the “Potash” which also overflowed quite often, At the top end of Walnut Avenue, now Seven Cottages Lane, stood “Villa Farm”, still there today, complete with the small pond which does not overflow now as it did then. It was a subsidiary of “Hill Farm”, which is further along the road. Both farms were owned by Major Norman Everett, a nice chap who used to ride around the area on horse-back. This farm is still worked today and is relatively the same now as it was then except for the horse pond which has now dried up, and the loss of a few hedges which have been removed to enlarge the fields. Of course, mechanisation has now replaced the horse power of yesteryear. The “Street” or Sherwood's Farm has already been mentioned elsewhere.

There was another arable area in the village which should be classed as a smallholding rather than a farm. It consisted of two fields, one of about twelve acres and another of about five acres. The larger area would produce some outstanding crops of wheat which was almost five foot high, making the straw ideal for thatching. These areas belonged to a Mr Joe Baker who also owned the “Street” meadow on which the houses in Playford Lane now stand.

Most of the fields in the village had names. I learnt them all from my grandfather who was a horseman during his working life. These names don’t mean a thing today, but as a matter of interest I recall some of them here, ‘Pokesys’, ‘Dogses’, “Clappeds’, “Whiteses’, ‘Stony’, ‘Gold Acre’, ‘Ballses’, ‘Gobberts’, “Norman Hill’, ‘Horse Pond Field’, ‘Little Pittol’, ‘Blox Meadow’, ‘Lacey Steps’, ‘Crankyhill’ and “The Round Field’ which was actually rectangular, probably named originally by some old farmer who'd had a few...

Every year a ploughing or ‘drawing’ match would be held, usually on the field opposite the ‘Falcon’ pub, Classes were open to anyone, including ladies, and competitors would come from miles around to take part, The field would have been previously measured up and marked out with white pegs at each end. Each competitor paid an entrance fee and would be given a plough with a pair of horses, the object being to draw out a straight furrow from a peg at one end to a designated peg at the other. Some furrows used to be spot on but others left a lot to be desired. The overall winner would receive a silver cup, the runners up receiving a copper kettle.

The Village School

The school used to have well over a hundred pupils in those days, split into four classrooms with five teachers. There were some bright boys there too I well remember one, Chunker Taylor he was called and he lived in “The Red Row" or Seven Cottages as they are known today. Chunker wore out more canes than anyone else in the school. His favourite trick was to use his catapult with a nice round pebble to hit the bell which was then situated on the gable end of one of the classrooms, He was quite an expert at this and would regularly entertain the occupants of the surrounding area with it, Ding, Dong, Ding. This same bell was struck by lightning in recent years and had to be taken down.

The infant’s teacher was a Miss Laura Beatrice Werts or as we cricketers used to call her. L.B.W. There was an open fireplace in the corner of the classroom and during the winter months she was always perched on the top edge of the fire guard roasting her backside. However she wasn't too bad a teacher and possibly not so stingy as some of the others. Standards 1 and 2 were taught by a Miss Stannard. She was a stingy old devil using a ruler to rap you across the knuckles or ears, She was intent on drumming it into you one way or another. Unfortunately I was not one of her favourites and I got more than my fair share of sore knuckles and red ears. A Miss Cicely Nunn was in charge of Standard 3. She was quite a nice lady and seemed to get results without the use of too much physical punishment. Finally to the Headmistress. a Miss Salter. She could certainly wield the cane as poor old Chunker Taylor found out on many occasions despite the sheet of cardboard discreetly placed inside his trousers. On reflection, I suppose that all in all they had a difficult job to do one way and another.

There was one particular boy in my class. no names no pack drill, who was a nice enough lad but was rather slow in learning which resulted in him receiving more thumping than most, but for all this, he appears to have come off the best of any of us, for today he owns his own business and has employees working for him.

I remember one lad, Jim Stone, a brainy boy who was always studying and learning. He would voluntarily take home loads of homework to do and eventually worked his way through to a scholarship. At the outbreak of World War Two he joined the Royal Air Force and became a member of air crew, only to be killed whilst on operations. I sometimes think what a waste of a good life it was.

The Windmill

There used to be a windmill situated on Playford Road where corn was regularly ground. It was owned by a Mr Alfred Dawson who also owned three sets of threshing tackle which were in regular use practically all year round. There were no combine harvesters in those days, He also owned steam ploughs, steam rollers, steam tractors and a steam wagon, all of which were in full-time use. His son Douglas carried on the business after the old boy died, but as combines came more into use and the internal combustion engined vehicles took over, the business declined and for a short time became a light engineering works. However the mill and workshops were eventually demolished and the cul-de-sac known as the ‘The Mills now stands on the site.

Rushmere Heath and the Heath Money

At one time the parishioners received an annual payment of what was known as the ‘Heath Money’ which was the income paid by the golf club to the Parish Council for the use of the heath. There were probably not many more than a hundred households in Rushmere at that time. I think that the last time the money was distributed each householder received 5/-. A tablet explaining the origin of the Heath Money used to be on the front of what were known as Tablet Cottages. It was placed on the front of the baptist chapel when the cottages were demolished.

During World War 1 part of the heath was taken over by the government and used as an army training ground. It was an area close to the present Heath Road and thousands of troops were trained there and so it became known as “Soldier's Ground’.

Sand used to be dug from the ‘little heath’, the area lying between Playford Road and Woodbridge Road, by a Mr Whinney. He owned a horse and tumbril and would transport the sand to building sites in the area. When I left school I went to work for a Mr Lillingstone who was a builder and scoutmaster of the Rushmere troop, through which he was referred to as ‘Skipper’. One day I was returning from an errand on which I had been sent, when glancing across to the sand pit I could see the horse and cart but no Mr Whinney. Looking more closely, I could see his head sticking out of the sand. He had been digging when a sudden fall of sand had enveloped him. I ran back to Skipper, raised the alarm, picked up some shovels and between us we were able to dig him out, much to his relief.

The Village Fete

Every year a fete was held on the Church meadow. The sporting events always attracted some well-known Ipswich athletes. There were also various sideshows including skittles and bowling for a pig and at one time a horticultural show was staged.

Church Cottages

There used to be a row of five cottages where the church car park now is. I remember that when I was attending the school as an infant, us children were dead scared to pass them in the dark. In one cottage lived a queer old lady (Miss Talbot) and on dark evenings she would stand at her doorway dressed all in white and ringing a little bell. It really put the wind up of us as we used to think she was a ghost.

Sunday School

Most village children attended Sunday school at the Baptist Chapel on Sunday mornings. Every Christmas we were given a party and during the summer what was known as the Sunday School treat. It was like a picnic and was held on what was then known as the ‘Pinetoft’ which was an area of parkland situated between Humberdoucy lane and Colchester Road where Winston Avenue now is.

The Football Team

Rushmere had a football team in those days (Rushmere United) and quite a good one it was too. The home ground was a meadow near Villa Farm. The team played in the Ipswich Junior League and usually finished each season in the top three. Sometimes local derbies were arranged with Kesgrave and Tuddenham. Whenever we played Tuddenham at their ground we always wanted to play the second half with our backs towards the ‘Fountain’ so that we could make a quick getaway if we won. Bathing in the stream which ran round the pitch could be quite an experience in January or February and was not to be recommended

The days are long gone when we used to play football with a tennis ball in the road in front of the chapel, placing two clods of earth at each end to act as goal posts. The only interruptions being the passing of a flock of sheep or the cows being taken to or from the meadow and occasionally the ‘Swift sure’ bus which ran between Ipswich and Bealings. Its name certainly did not live up to its reputation as it frequently broke down and on occasions when it was full we had to get off and help to push it up Woodbridge Road hill. The fare was fourpence return.

Entertainment

The Salvation Army band would visit the village occasionally on a summer's evening to hold an open air service near the off-licence. It was quite amusing to see the men after a hard day’s work in the field sitting around drinking their mugs of beer and joining in the sing song.

Harvest time

At harvest time we would spend the whole of our summer holidays in the cornfields. When the corn was being cut we would chase and catch the rabbits which ran out of the corn. If it rained we would shelter inside one of the shocks (stooks) of corn which would be set up in order for the corn to dry before carting. It acted like a thatched roof allowing the water to run off. Later, after the corn had been carted to the stackyard, we would go gleaning on the fields, picking up any loose pieces of corn for feeding to the chickens,

The people of the village

At the time of which I write the most common surnames to be found in the village were Rush, Mann and Boast. I recall at least four families of Rush and all were quite large, In one particular family of Rush’s the best known boy was Sonny. He was the local thatcher and he thatched all the hay, corn and straw stacks for several miles around. He was also a good touch for an odd rabbit every now and then, which provided a Sunday dinner. His brother, Bill, was an ex soldier having served in France during the first world war and was quite a character. Then there was Stanley, commonly known as ‘Hawk’, who worked for Joe Baker. He was a comical chap who enjoyed a pint of beer and was an expert on the use of the catapult, He very rarely missed hitting whatever he aimed at whether it be hare, rabbit or pheasant and his mother was kept well supplied with meat for the table. I remember one night at the ‘Falcon’, After a few drinks he went outside to answer the call of nature, On his return his face was covered with what appeared to be blood and he seemed to be limping badly, “What the hell has happened to you” someone asked, “A damn great bloke out there beat me up” he replied. Everyone rushed out to retaliate on Hawk’s behalf, hut nobody was to be seen or heard and on returning to the bar after having a good look round in the pitch dark, there stood Hawk with his face as clean as a new pin laughing his head off. We then discovered that the so called blood was actually tomato ketchup, Another brother was Tom, “Tucker’ to the locals. He was rather more serious, liked a drink, a flutter on the horses and for a pastime kept ferrets which he used to carry around inside his shirt from where they would crawl out around his neck. The youngest brother was Cyril who entered the church and later became the vicar of Hoxne in Suffolk, There were also two sisters, Louise and Bonnie. Alas, they are all gone now. but, Sonny's two daughters Pamela and Janet still live near the chapel.

Then there was a Harry Rush who kept the off-licence for a time. He was a golfer and a well known pigeon fancier. His son Bill was a great friend of mine.

There were quite a few Rush’s living at Red Row (Seven Cottages) in those days including Tom Rush who was the professional at Rushmere Golf Club. Another was Dick Rush, also a golfer. Then there was a Charlie Rush. He went round delivering milk from a horse drawn milk float. The milk was contained in churns and would be measured out on the doorstep. Charlie was a red faced jovial character, his favourite tipple being Beano Stout which he used to drink in copious quantities before attempting to ride home on his bike on which he very rarely steered a straight course.

The Mann family lived in a very small cottage on Playford Lane, There were three boys, George, Billy and Reggie, and two girls. George was head horseman to Major Everitt, Billy was a cowman, while Reggie, who played golf, worked somewhere in Ipswich.

Another Mann family lived at Red Row. There was Tom who worked at Heath Farm and Stife, who at one time was landlord of the local pub where beer cost two pence a pint. I expect there are many people who wish it was that price today.

Boast was another common surname in Rushmere when I was a boy. Emily Boast took on the shop when my grandparents gave it up which suited her admirably as she was looked upon as the village gossip and she lived up to that reputation very well. No one’s movements or business escaped Emily, but for all that she was a likeable old girl with a heart of gold, Her husband’s name was Arthur, who was a horseman at Street Farm. They had a son Billy who was very popular, a good gardener, footballer and played the organ at the Baptist Chapel for many years and a daughter by the name of Elsie who used to take me to school when I first started. Arthur’s mother, Granny Boast as she was called, ended her days in Playford Lane and was over one hundred years old when she died, being reasonably active to the end.

And so to the Farrows who were all connected with horticulture in one way or another. Charles or ‘Ching’ as he was known worked for Joe Baker, driving a horse and cart transporting a variety of things around and he slaughtered the pigs at the local slaughter house. Alf or ‘Fudge’ as he was known worked as a gardener and has been a keen golfer all his life. Then came Jack, also a golfer who worked on the Ipswich Parks and still lives in Ipswich. Reggie, the youngest once worked on the Ipswich Parks but he moved away and I have not heard of him for several years.

Another family worthy of a mention is the Jay’s. There were four boys and two girls, The old man Bill and two of his sons, Horace and Freddie, worked together and once owned the nursery which used to be in Westbury Road where they specialised in growing tomatoes and pot plants. Sidney or ‘Boxer’ used to keep hundreds of chickens on a piece of ground on which Chestnut Close now stands, He reared them from day-old chicks right through their egg laying period and into old age when they would eventually be killed off and sold for the table. He was quite a character, tight with his money, and was always working, very often well into the night. He was always to be seen, or heard, riding around on his bike, steering it with one hand and playing a mouth organ which he held in the other. Alfred, the youngest boy worked in the office at Churchman’s tobacco factory in Ipswich. There were also two girls, Annie and Freda,

Finally there was the Turner family who like me lived in Holly Lane but we were not related in any way. They were very nice people and the daughter, Lily, helped my mother a lot while I was in the service during World War Two. Lily had three brothers, although I do not remember the eldest one so well. Fred who worked at Dawson’s Mill was a part-time fireman and could turn his hand to almost anything. Eric took up butchery and worked at various shops in Ipswich. Shortly before she passed away, Lily went to Australia for a holiday and celebrated her 80th birthday on the plane. The passengers and crew joined in and gave her a party.

In a big house known as ‘The Lodge’ which is near the church lived Mrs Mason and her three daughters Nancy, Angela and Monica, one of whom was a missionary. They used to run a clothing club into which the village people paid a small amount each week and once a year received vouchers to spend at one of the large stores in Ipswich. This was the only way that some people could afford to buy clothes.

The King family owned Rushmere Hall Farm. Benjamin was the guvnor. His wife was in charge of the Chapel. The son, Everett King, was an auctioneer and there were two daughters Rachael and Margaret who ran the local Girl Guides. The farm stood about a hundred yards from the school and as there was no water supply at the school, every day the older boys would be sent to fetch three pails of water from the farm which was used for washing and drinking. As a reward each boy would receive a bar of chocolate at the end of each term.

I can remember Rufus Crapnell the blacksmith and his father ‘Blackberry Joe’. I spent many happy hours with my grandfather watching them shoeing horses and putting tyres on cart wheels. Rufus had a son, Desmond, who was looked upon by the other boys as the village idiot.

I have known Rushmere village for most of my life, having lived there since 1929 prior to which I spent all my school holidays there when I stayed with my Grandparents. The day following school break-up I would be taken to Rushmere and fetched away again the day before school started back.

At that time Rushmere was indeed a village, with its pretty little dormer-windowed cottages, most of which have now, alas, disappeared. Although only three miles from the centre of Ipswich, it seemed in those days to be at least fifty miles from the nearest town, a completely agricultural area where the wonderful scents of the countryside lingered in the nostrils for many years after it sadly became an urban area. Such is the price of progress. when a country village with all its traditions, natural beauty, its crafts, characters and family connections are lost for ever to be replaced with bricks, mortar and concrete. An area where for hundreds of years the population had lived and worked, usually under primitive conditions compared to modern living, content with their lot, happy in their environment, friendly and happy-go-lucky, wiped out in a few short months under the bull-dozer to satisfy man’s desire to own his own home in this so-called affluent period of our country's history.