THE LIFE AND TIMES OF FRED HARVEY

THE LIFE AND TIMES OF FRED HARVEY

I was born in a small terraced house in Ipswich on the Woodbridge Road near where Woodbridge Road meets Spring Road on 21st February 1923. My father’s name was Frederick Allen Harvey. My mother’s name was Emma Harvey. Her maiden name was Beckett. Her father worked as a stevedore at the docks. My father worked on the Great Eastern Railway in the loco sheds off Croft Street, repairing the rolling stock. He died at the age of 25 after an accident in which he had to have his legs amputated,. After that I was brought up by my grandparents Gerald and Alice Harvey. Her maiden name was Heffer, and she came from Framlingham. I have always wondered how they lived when they were young as they never spoke much about days gone by, so I will try and tell you about mine.

My mother and father at their wedding

As a schoolboy I played the usual games when they came in to season There was a time for everything. There were hoops, spinning tops, marbles, conkers, pop guns, clappers, cigarette cards and football in the road. Toys we seldom had. We hung up our socks at Christmas time for Father Christmas, and got an orange or nuts or a few sweets if we were lucky.

My father and mother

My father, mother and me

My father at work. He is the one with his arms folded

My grandfather and grandmother

My earliest recollections are of my grandmother who I called Nanny, and of my grandfather. One thing that I do remember was my first day at school. Nanny took me to school and handed me over to the headmistress, and when all the parents had left, she took me by my hand and walked to the centre of the hall. She put her hand on my head and said "Will all the boys and girls get in line behind this little boy”. Then I felt a pain in my tummy, and I made a silent, but nasty smell. The headmistress said "Will the little boy or little girl who made that nasty smell please go to the lavatory". Nobody moved. That was my first day at school.

When I was eight I went into the boys school next door. We had a teacher called Miss Gilbert. She was very strict and would give you the cane for the most minor thing. She would say "Put your hand out", and if you pulled it away before it hit you, it hit your leg instead, then she made you bend over a chair and gave you two whacks on the bum.

When I was nine I went into Mr Clanfield's class. He was a younger man. Sometimes if he caught you doing something wrong he would throw a piece of chalk at you and he seldom missed. He used to take us for football in the park on Thursday afternoons.

Just before Easter grandmother said "I am taking you to see your mother. We will go on Easter Friday and you will meet your new dad. She wants you to stay with them at weekends". I remember that first trip to Henley. We got on the bus at the old cattle market. It was snowing hard and we got off the bus at the Cross Keys public house and walked up the Barham Road. On the right stood a row of small terraced houses. One was a shop, my mother lived in the middle one, and a Mrs Rush in the end one.

Inside the house I met my mother. She was a stranger to me. She said I could go and stay with her after school on Fridays and go back to Nanny's on Sunday afternoon. We did not stay long as we had to get the bus back to Ipswich. On the way back Nanny said "You never met Uncle Chris, your new dad. He was working. He looks after chickens on the farm".

Aunt Olive

After the Easter holiday I started back at school and on Friday when I got home Aunt Olive was there. She was grandmother's daughter. She said "I will take you to the Cattle Market and put you on the bus. We must hurry, it goes at five o'clock". I got off the bus at the Henley Cross Keys, walked slowly down Barham Road, and knocked on the door.

My mother opened the door and said "Come in and sit by the fire. We'll have tea when Dad comes in”, so I sat down. She asked me how I liked my school, then she went out of the door into a little wooden shed to get the tea ready. An oil lamp stood on the table. That was the only light there was, there being no gas or electricity. She cooked on the fire and on an oil stove. In the room were the stairs. She said "Your bed is at the top of the stairs".

My stepfather, Chris Harvey

The door opened and this man came in. He was not as tall as my mother. He said "Hello Fred", and I also said "Hello". He said “I have to go back to work tonight. Would you like to come and see the baby chicks that hatched today?" I said "Yes", and he said "When we've had tea, off we go". After tea he said "Put your coat on if you’re coming”, so off we went. He said he had about four hundred day old chickens in the huts we were going to. He had to make sure that the oil lamps were OK and that the wicks were not smoking. If they did they might get too high and set fire to the huts. Soon we were there. There were several huts and inside there were little runs full of baby chicks making a heck of a row. They were all being kept warm by what was known as a hoover. It was a little oil lamp with a guard round to stop the chicks burning themselves. It was shaped like a little bell tent with a screen round it so the chicks could not get out.

When we got back, mother said it was time for bed, so I went up the stairs. There was the bed but no bedroom. The bedroom was the landing - there was only one bedroom. Next morning mother said I could go and get the milk, it would give me something to do. She told me to go to Chiddock’s Farm, on the Henley church corner. It seemed even further coming back! I got the milk in the milk can. I had to ask for skimmed milk, and it cost one penny.

Then came Sunday and time for me to go home, as I called it. I got off the bus at Ivry Street, walked down Berners Street, along Norwich Road, Clarkson Street and Bulwer Road to 23 Rendlesham Road. Grandmother wanted to know how I got on. I told them I went to my work with my Dad. Grandfather shouted at me "He is not your father ! Don't you dare say that here again!" so in the future when I was with mother I called him "Dad" and with Grandfather he was "Uncle Chris". Sometimes I forgot at both places, then I was in trouble. After that I went home every weekend.

Aunt Eva

Soon after me going to Henley, Aunt Eva came to live with us. She was Grandmother's daughter and she slept in bed with me. I didn't go a lot on her. Sometimes she would come to bed and say "Are you asleep?" and if I said no she would pull back the bedclothes and whack my backside. If I didn't answer I would still get a whack for pretending to be asleep. Sometimes she came in late and if I was asleep she would push me back against the wall and read a book.

Then she joined the Salvation Army, Bramford Road, and she bought me a red Salvation Army jersey. That meant I had to go to Sunday school, so I had to run all the way from Ivry Street to change into my jersey and get to Sunday school and then the afternoon service. Soon I joined the singing company. That was alright. Then I joined the young peoples' band and my instrument was the big base - it was nearly as big as me. I took it home to practise, but Mrs Ellenoar kept complaining about the noise I made and said I must give it up.

Aunt Eva got a job. Grandmother told me "She is going to work for Police Inspector Simpson, he lives in Brookshall Road, and she will be living there, she is going to be his housekeeper". Soon after that Aunt Eva moved out.

One evening I was in bed and I could hear the boys in the road. My Grandfather was in bed snoring. I thought, if I got into the back bedroom, which was a very small room with a small window on the other side of the stairs, and if I got through the window and down on to the lavatory roof, I could then get down on to the old tin shed, which was the bike shed, and I would be able to jump down, and run up the passage and out. Next day after Grandfather had gone to work, I went upstairs and tried it, and it worked. After that I was often out with the gang. Sometimes we went up town.

In Tower Street was Pooles Picture Palace, they had mostly western films - Buck Jones, Hopalong Cassidy, The Three Stooges, those sort of films. We went round the back of Pooles, next door was Lyons Bakehouse, round the front in Tavern Street was Lyons Restaurant. In front of the Bakehouse was a room where they put the cakes and buns. We looked through the window, no one about, so in the door, nick a cake and out, into Pooles lavatory, (the other boys had done it before), then go to the other door, one of the boys had a look to see if the old attendant was there, he couldn’t see anyone so we all walked to the back of the cinema. There was a platform for people to stand on when all the seats were taken, so we just stood there and watched the films.

Tuesdays were market days, when the farmers brought their cattle to be sold. If they were sold to local butchers, then they were driven along the road by drovers. They would be taken to the slaughter house up the driveway at the side of the Spotted Cow Public House on Bramford Road. Sometimes we gave the drovers a hand and they would give us a penny each. Sometimes we helped drive them to the railway sidings. We would drive down Portman Road, into Princes Street.

Just before you got to the bridge stood Pauls Maltings, and beside it there was a rough track down to the river and the railway, and we helped get them into cattle trucks. Most of the drovers knew us, and for helping them get the cattle into the trucks they would give us two pennies. One week we drove for a fresh lot of drovers, they let us help them and then when we had finished they told us to clear off . A few weeks later we saw them again, we waited outside the market gates, they had several bullocks and as they came out on to the road we waved our sticks and shouted at them. Instead of going down Portman Road to the railway two of them turned and went up, and we chased them and they got up to Barrack Corner. We never went to Barrack Corner, we ran down Handford Road, we never saw them after that.

Sometimes we went scrumping, we would go after apples in peoples gardens. Dick Parker who lived in Bulwer Road had an old cart and he went round selling fruit and veg, and if we got enough he would buy them. Bramford Road and London Road district were patrolled by a Policeman on a horse. Sometimes someone would spot us and tell the Policeman, if we spotted him we would scarper, and he would follow us on his horse, chase us up and down a few roads, then stop, then we would stop running. He would sit up on his horse, shake his white gloved fist at us, then give a wave and go away.

Every year in Ipswich the poor children’s outing was held. It was for the kids whose fathers were out of work, and kids who had no father at all, so I was one. All the firms in Ipswich decorated their lorries, and people who had cars. We had to go down to Alderman Road and have a ticket pinned on your clothes, then we were put on a lorry or car, and away we would go to Yoxford. There the Lords and Ladies came and looked at us. As we left Ipswich the roads would be lined with cheering people, and it was the same coming back, but we enjoyed ourselves. We were given sandwiches, and the rich folk would throw us pennies.

When he had his holiday, Grandfather sometimes hired a beach hut at Felixstowe, on what was called the wireless green. We went from Ipswich station. Coming back at night was chaos, there would be a queue of people stretching from the station almost to the beach. When the train came in those on the platform grabbed the carriage door and hung on to it till their family were aboard. When all the seats were taken they still kept pushing to get in. Sometimes it was almost impossible to shut the door. Then the train would move out and next stop Town Station, more queues, and they would try to get in as well. There would be people sitting on people's laps and kids being passed around crying. There were no corridors on trains then. When the train stopped at Derby Road station we had more chaos sorting the families out.

The amusement park at Felixstowe had not long been built, and in the middle of the park was a big lake. In the centre was an island, there were trees and rocks on the island, and a lot of monkeys. There were canoes on the lake and for sixpence you could paddle a canoe around the lake and feed the monkeys, but it didn't last many years, I think it was about two years, then we had a very cold winter and all the monkeys died.

They also had a zoo, one lion, one tiger, and snakes. They had a stage where about six black men with bones through their noses did a war dance, and ate flames of fire. To see the rest of the show you paid sixpence to go inside, I went in, they shouted and did this war dance, and danced on broken glass. Then they came round for more money, (you already paid sixpence to go in), and the show lasted about fifteen minutes.

Along the beach there were motor boats, and beside each boat shed there was a man shouting “Any more for the motor boat? round the bay and the Cork lightship". The Cork lightship was anchored about three miles out at sea. When it was foggy, its horn would keep blowing, and it had a lamp at the top of its mast which kept going round and round and warning other ships.

In 1933 my mother moved into a new council house on the main road in Henley. It had a kitchen, front room, and three bedrooms. Electricity had not yet reached Henley, and they still had the oil lamp hanging from the ceiling. Water had to be fetched from the pump which was four houses away up the road. The lavatory was still a bucket which you had to empty when it was full into a big hole which you had to dig. The house was near Dad's Father and mother. Her name was Liza, her hair was all different colours, even a streak of green. She dyed her hair with something that she boiled up and rubbed on her hair. It was grey, ginger, black, white, yellow and brown all mixed up. The house had a large garden, and next to the garden were a few hundred chickens, belonging to Millicent Jacobs, he (yes he), lived with his father and mother and his sister Joyce.

Dad bought a wireless set, it was called a KP. Pup. It was a small box with three controls, it had valves. It was on a shelf near the window. The aerial went through the window frame, up to the roof of the house, and then it was fixed to a high pole at the bottom of the garden. The loudspeaker was round in shape and hung on the wall indoors. The radio did not start until 10.15 am every morning and that was a short religious service. The stations were London Regional, Daventry and London National. That never came on the air until 5.15 pm, with a dance band, Jack Payne or Beaty Hall. The licence fee was ten shillings a year.

In 1933 1 was ten years old, and my Grandad bought me a second hand bike, I could ride a bike. I used to ride my Grandfather's, his was a big bike. He used to get on it by putting his left foot on the step which was used to tighten the spindle of the wheel to the bike frame. With his foot on that he would scoot along with his right foot until the bike got going hard enough for him to take a leap up and into the saddle. Lots of bikes had a step, you could take people on your bike. You got a carrier which you fixed above your back mudguard, then they could sit on the carrier, or put one foot on the step and kneel with their right knee on the carrier. I rode Grandfather's bike by putting my left foot on the pedal and putting my right leg through the frame under the crossbar to the right pedal, and when you pedalled you went up and down with the pedal. Now I had a bike I could ride to Henley, and I was old enough to help pay for my keep.

In the autumn I went brushing with the other boys in the village. There would be Doctors and other well to do people, and they all went shooting. We had to walk through hedges, ponds and fields in a line scaring the pheasants, partridges, rabbits, hares and pigeons. We had to make them fly towards the guns. After they shot them down we had to pick them up and carry on with the beat. The shoot lasted all day, we stopped at midday and we would have sandwiches that had been brought in special, and there would be beer as well. All that had been shot would be put in a big basket, then we carried on. By the end of the afternoon your arms would be aching with the weight of the birds and rabbits.

One day I had a pheasant, holding it by the neck, I had other birds and a rabbit. I came to a hedge and the pheasant got caught up, so I gave a big tug and pulled the bird through. When I looked at my hand I only had the head, the rest of the bird was in the hedge. I left it there and walked away. When they finished for the day all that had been shot was laid out and shared amongst the guns, and what was left was shared amongst the beaters. Then we would eat the rest of the food and drink more beer, and by this time us boys were feeling a bit silly. Of course, that made the Doctors laugh and they would tell you to drink some more, then we got paid, five shillings for all day, two and sixpence for half a day.

Sometimes in the summer I earned money in the harvest field when they went carting the corn. I would take the horse and wagon into the field, one of the others would bring the other wagon, then it would be three men left with the wagon to load. There would be one in the wagon, and one each side pitching up. When it was loaded I would take it to the stockyard to be stacked, and take an empty one back. We worked from early morning until dusk, then the horses had to be taken home and have the harnesses taken off. Then they would walk to the pond, and stand in it and have a drink. When they had had their fill they would come out, and not before. While they were drinking I had to fill their feed box up, and then go home. This was not every day, only when they wanted to get the corn in.

The years seemed to fly past, and my Grandmother would say "What are you going to do when you leave school?" I would have liked to have gone on the railway, but there wasn't a lot of work for young boys. There wasn't much for the men, unemployment was very bad. Men would wait outside the factory gates waiting for someone to get laid off, so when the time came to leave school I hadn't a clue.

And now it was time to start thinking about leaving school. Aunt Eva came to Grandmother’s and told her that Mr Berne, the cabinet maker, was looking for an apprentice boy. She had told him about me and I should go and see him. I went along to see Mr Berne's factory. It was along the Wherstead Road, just before you got to Bourne Bridge. I found him in his office, told him who I was, and he asked me "Do you want to be a cabinet maker?", I said "Yes”. “Well”, he said "It's a five year apprenticeship and your parents will have to come and see me, and we'll sign the papers. Do they know you've come here?" I said "No". He said "I think you should go home and tell them, after all, they may not be able to afford to send you here". So I left him, and called at Aunt Eva's shop in Wherstead Road. I saw her, and her friend Jimmy Briton was with her and he said an apprenticeship could be a very expensive thing. Then I went home to Grandmother's, “You can ask your mother" she said. The next night I went home to Henley and saw my mother. I told her what I'd been told, she said "We cannot afford to pay for your apprenticeship. While you’re at school I get two and sixpence a week, and now you're fourteen I shall lose that. You will have to get a job with a wage".

Sunday at Grandmother’s, Aunt Olive and her two boys came to tea, and she said to me "Charlie Blake wants a boy to help him on his greengrocery cart”, so after I came out of school on Monday I went to Allenby Road and met him. He had a withered arm and walked with a limp. He said "I want you to help me with the cart and serve some of the customers". As this was my last week at school I told him I would start next Monday.

The rest of the week seemed to pass quickly, and when I got home from school on Friday, Grandmother had been crying. She said that she had got a letter from my mother, to say that now I was growing up it would be best for me to go and live with her, as I had brothers and was one of the family. I went home to Henley feeling very sad. I often think of that ride I made going up the Valley Road. On Monday morning I biked to work for the first time. I called at my Grandmother's first, and then to Charlie Blake's. My first job was to load up the cart with greengrocery, and then we started off. The cart was heavy. He told me which houses to call at and get their order, and he got it ready while I went to the next house, that's how we carried on. On Friday I got my first pay. I called round my Grandmothers every night, then I went home. When I got indoors my mother said "Did you get paid?" I put my hand in my pocket and pulled out seven and sixpence. My mother gave me sixpence back. I made up my mind I would not be with Charlie Blake long.

On the third week with Charlie Blake I was told by a Co-op milkman that the Co-op wanted boys, so during my dinner hour I went down Sproughton Road to the Co-op dairy. I met Mr Creswell, he asked me a few questions, then he said 'When can you start?" I said "Monday". He said 'The wages are eleven and sixpence a week. Start at five, go home when you have finished your round". I said 'Thank you" and went back to work. When I got home I told my mother I had got a job on the Co-op milk, ten shillings a week, start at five. She said "You will have to be up at four". I hadn't realised that. I told Charlie I was leaving, he didn't say much, and on Monday morning at five I started on the milk.

I went on a lorry the first week, Colchester Road, Rushmere Road, Kesgrave, Martlesham and Valley Road. The next week I went on a horse and cart, Bramford Road area. The third week they gave me a big cart, two big wheels, one each side and a small one at the back, and it was loaded up. My first call was Kingston Road. I remember pulling it up Sproughton Road. It's a bit of a hill, and I had a job getting it there. I stuck that for a week. I got my wages Friday, went in Saturday, delivered the milk and went back. I saw Mr Creswell, I said 'Can I leave now or do I give a week’s notice?' he said 'There's the gate" so I got my bike and went. I called at my Grandmother’s, then I realised what I had done. She said "I don't know what your Mother is going to say. Go up the town, perhaps one of the shops needs an errand boy".

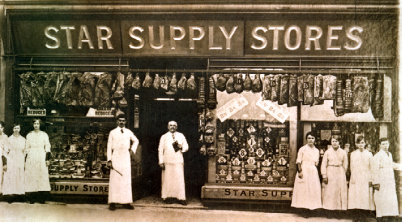

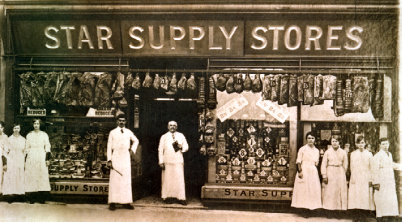

So I went up the town, I walked round the town, down some of the streets, and finished up in Upper Brooke Street. In the window of the Star Supply Stores was a card, boy wanted. I met Mr Osbourne, the manager and he told me what the job entailed. Every morning clean the shop windows, take off old bills, polish the marble outside the shop, polish the brass and wash the shop floor. Every Monday scrub behind the bacon counter, then take out any orders that came in. Friday, stay in the shop as long as there are customers, Wednesday, half day. Wages fifteen shillings a week. What a difference from a few weeks ago! I couldn't believe it, it seemed such a lot, and I started at nine Monday morning.

I went and told Grandmother, she said "Well, that's better than getting up at four in the morning. Now you can go home and tell your Mother", so off I went feeling a lot better. I never went anywhere over the weekend, I hadn't any money. I kept thinking I'll have some next week, so I spent most of Saturday afternoon and Sunday standing on the Henley Church corner with the village boys and girls. We played darts in the harness shed at Chiddock's Farm. That was all there was to do.

Monday morning I arrived on time. There was Miss Brown, Miss Metcalf and the cashier, I can't remember her name. There was Mr Potter on the bacon, Mr Osbourne the manager, Mr Tanner and another man.

I had a bicycle with a big carrier on the front to take parcels. Then there was a tricycle, that was like a great big box with bicycle wheels, one each side, and handlebars fixed to the back of the box to steer with. Under the box was an iron bar, and fixed to that were the crank, pedals, and back wheel. Another bar went up and on that went the seat. Under the seat was the hand brake. It had a fixed wheel. That meant you could not freewheel going down hills. The box had a door in the front where the parcels went, then there was a railing round the front of the box so that the parcels carried on top did not fall off.

I cleaned the shop windows every morning, polished the brasses and the marble, and scrubbed the shop floor. I scrubbed behind the bacon counter, and I found two threepenny bits in the crack of the floorboards. Mr Potter said “Give them back to him, boy, he put them there for you to find. He's just testing you". That carried on for a week or two, then I never found anymore.

One day I had a full load to go to a shop near the Royal Oak Public House. Inside the box was full and the top was stacked up. When I got on the seat I had to look up as I couldn't see in front properly. I got up Bishops Hill, and I decided to have a rest. I put the back wheel against the curb as I thought, but somehow it started to move back. I tried to grab it, but it went back, then the front swung round and it toppled over and out came all the stuff round the lamp post. There were glass jars of ox-tongue, some broken, bags of sugar, some burst, jars of jam broken. I managed to get the bike up but the back wheel wouldn't turn, so I left it and walked back to the shop.

I expected to get the sack, as I entered the shop Miss Brown said "He knows all about it. A lady was in a tram and she saw it, and the driver said you were overloaded". I went into the back room of the shop and there he was. He said "Why didn't you tell me it was too much for you?" I said "You said they were all for one shop, and you put some of them on the bike". "Go with the van driver, take a broom and shovel" he said, but when we got there it was only the broken stuff left. We put it all in the sacks, and with the help of another man walking up the hill we got the bike into the van and took it to Nightingales cycle shop on Felixstowe Road. I waited till he fixed the bike, then I rode back. The van took the order next time.

In those days the carrier used to come to town every day. He either had a van or covered in lorry, or some had a horse and wagon. They would leave their village. If you wanted them to call, you put up a notice outside. For instance, Pallant was the carrier from Debenham. If you wanted some shopping from Ipswich, you put the board up in your front garden with the words 'Pallant to call' then he would call round. If you wanted some shopping done he would do it. You gave him the list and some cash to pay, if it wasn't enough you paid him when he returned. When he got to Ipswich he would call in the shop with the list and pay, then they would do the rest. If they wanted groceries from the Star Supply Stores where I worked, the girls would get the order up and I would take it to his lorry which was parked at the Blue Coat Boy, Tacket Street. All the carriers put up at different public houses in the town. It got quite hectic if you had a lot of orders and they were all different carriers, and they all left Ipswich at 2.00pm. The Eastern Counties buses used to take parcels on their buses. The conductor would come in with the order. In those days all the buses had conductors.

One day I was going along Bramford Road when I saw a notice Boy Wanted, at a greengrocers shop owned by Herbert Rooke. I went inside the shop and asked about the job. He said "Fifteen shillings a week”. I said I could start next week. I gave my notice in at the Star Supply Store. I wasn't sorry to leave there as the van driver called at Liza Harvey with her groceries every week, and she would ask about me, and he would tell her all about me, even told her my wages and then she told my mother.

On the following Monday I started with Rookie, as everyone called him. He and his wife were very nice people to work for. He had a daughter, Molly. My first job was to put all the vegetables outside the shop, then he gave me a book with all the names of the customers who I had to call on and get their orders and went back to the shop and got them up. He had two bikes, one he had just bought. He said "That’s yours", it had a small wheel in front, and a huge basket, you could get some orders in that!. I delivered the orders, and when there were no orders to take out I served in the shop.

Then one day Rookie said 'I'm thinking of getting another boy. You will get the orders the same and take some out when we’re busy, but there are other jobs you can do. Do you know anyone who wants a job?" I knew one lad I used to speak to on the rounds. His sister lived in Windsor Road, so I went round to see her and told her to tell him if he wanted a job to come and see me. He did that and I told Rookie, and he got the job. Mrs Rooke called him Sunny Jim, after a while everyone called him Sunny Jim.

Rookies father had a greengrocery round. He had a barrow, and he called in at the shop every morning to get his stuff to sell. He liked his beer and smelt of it. While I loaded him up he would keep saying 'Give us extra, I'll see you all right". so I gave him a bit more on all he had. He gave me two and sixpence, that was half a crown, a lot of money in those days.

When peas were being picked in the fields, Rookie would buy them cheap. In the afternoons I would go round with a big barrow, and a handbell which I had to ring, and I would call out as loud as I could "Garden peas, lovely fresh garden peas". I also made a few bob for myself. Then there was strawberry time. They were sold in little baskets called punnets. The basket would be loaded with punnets, and I also took a few empty ones, and once I was away from the shop take a few strawberries from each punnet and fill mine. Off I would go ringing the bell and calling “Cheap fine strawberries, all ripe". In those days a lot of people made their own jam, and I would be sold out. I liked working for Rookie, I always had money, and life was good.

When I got home to Henley most evenings I went up to the church corner, the meeting place where the boys and girls met. Sunday evenings some of the boys rung the bells at Henley Church, and I soon learnt to ring the bells. Not many went to church. There would be old Billy Pearson the parson, he gabbled on, you never knew what he was talking about. There was Gordon the organist and Ted the parson's boy who lived in the vicarage, and he came out with us boys. Then there would be about five or six in the church. The fire to heat the church was under the floor, and the flues were outside the church just above the ground. I remember the day when old Pop Brown had lit the fire, and two of the boys put rags in the flues and smoked them out of the church.

One Wednesday afternoon Ted and I had decided to go to the pictures to see the film White Feather. Audrey Rae came along, she was always after me. She wanted to come with us, but we said no, then we left our bikes up against the church wall while we went to the shop. When we got back to our bikes mine had a flat tyre and Audrey was laughing. Ted shouts "Grab her!!" so I grabbed hold of her, then Ted got hold of her legs, she screamed and struggled but we took her round the back of the vicarage. There was a bonfire alight and he gave it a kick and it smoked. He said "Let's get her clothes off", she struggled, she had not got much on as it was summer. He said 'We'll warm her arse". I held her under her arms and he had her legs and we swung her over the smoke. She shouted and swore, then Ted let go of her legs, I let go and she stood up. She smelt smoky and looked very wild, "You rotten *******" she said.

Little Audrey was more worried about going home in a mess, she said her Dad would kill her, but I don't think old Ted Rae her father would. I reckon he would have laughed his head off, he was that kind of chap. He liked his beer and he was nearly always happy. We went into the kitchen, old Billy Pearson was in his study, and Dolly Creasy had gone home. There was a kettle beside the fire with warm water. She washed her front, and Ted washed her back, then we washed as we looked a bit ruffled after wrestling with little Audrey. In the end we said she could come with us, and she could come in the future as well.

The talk of war was in the air. This time it was Adolf Hitler of Germany. In 1935 the Italians had invaded Ethiopia, in 1936 we had the Spanish Civil War, and now in 1938 Germany had marched into Austria, and on October Ist 1938 they had marched into Czechoslovakia. It was soon after that that everyone had to collect their gas mask. As I had lived in Rendlesham Road I had to go to London Road school to get mine. By now we were having Air Raid practise at night. There would be RAF planes flying and searchlights would be trying to spot them, then it seemed to be forgotten and life went on just the same. I still worked for Rookie and my wages were a pound a week, that was good considering Dad at Henley worked forty eight hours a week for one pound, five shillings a week and I was getting extras.

Then, I remember it well, Rookie had bought a car, and was taking Mrs Rooke to Yarmouth for the day. He asked me would I look after the shop Sunday morning. It was the 3rd of September 1939, it was about 12.00pm, there was no one about and everywhere seemed quiet. Then Mr Tye came in the shop for fags. He said "Have you heard the news?" I said 'No". 'We are at war with Germany, it's a sad day, a sad day", he said, then walked out of the shop shaking his head.

I thought I had better get home to dinner, so I put a few tins in my cycle bag for tea, locked the door, and went round to see my Grandmother, I always went round there before I went home. She didn't know we had declared war, and it upset her. Then off I went home. As soon as I got in I told my mother about the war, then the sirens went off. I remember my mother saying "Blimey, they haven’t wasted any time!". Soon after the 'All Clear' sounded. From then on all windows had to be blacked out so as not to show a light at night. Bicycle lamps had to have a very little hole in the front, car lights were covered, and there were no street lights in town.

About three weeks after the war had started Rookie said "Granger Bennett wants to know if you want a job, one pound ten shillings a week?”. Granger Bennett was the biggest window cleaner in town. He had three carts, each with a gang of four men. He did most of the big buildings. I started Monday morning. We did three small shops on the way up to the town. We stopped at the Electric House, Crown Street (it's still there now). It was my first job and I was told I'd get used to high buildings, so up went the three way extending ladder, it took three men to get it up. You pulled it with ropes. The first time it seems a long way to the top, and the ladder sways. I did it but I didn’t like it. Then we went to Lloyds Bank on the Cornhill and cleaned inside and out.

Opposite Woolworths stood a new store. The Lyceum Theatre had been pulled down and this huge building had been built. It was called Hills and Steels. To clean the top windows you had to put on a belt and hook it onto the window frame, then hang out and clean the window. I can tell you it's a horrible feeling the first time. I stayed with Granger Bennett for about two months, then a man I had spoken to many times, (he worked for himself as a window cleaner), came up to me, he said "Ever thought of going on your own?" I said "No". "Well" he said "I’m going to join the Fire Service, that will get me out of going in the Army. If you do the shops my wife will pay you two pounds. You can do the other rounds and any other job you want and the money's yours". I said "It sounds alright to me, when do I start?". "You can start next Monday" so I said "OK". On the cart with me was another young lad, he had been there longer than me, but we palled up. I told him "I'm finishing up this week". He said "Well, I've had enough of old Granger. I think I'll do the same, I know where I can get another job". Midday we stopped for dinner, we had our sandwiches on the cart. Then Neale my pal said "There's a good picture on at the central this week, let's go this afternoon", so off we went. Next morning Granger Bennett went mad, and when he asked where we went and we said the pictures he was worse. "You can finish Friday, the pair of you!!” he raged. He was a miserable old man, I knew his wife. I delivered there with Rookie, and she was a very nice lady, but he was not very nice at all.

On Monday morning I got the cart from Peter's Ice Cream Yard where it was kept in the Rope Walk, and called on Mrs Sadd. She was the wife of Bob Sadd whose round I now had. She gave me the list of shops, houses and Public houses and I set off. My own boss, what a difference from my first job at seven and sixpence. My first job was Weaver to Wearer, next door to Woolworth's. Then Bernies the ladies shop on the corner of Brooke Street. John Phillips was a big shop. It was a ladies shop, several girls worked there. I had finished the town by ten, then started on the houses up Westerfield Road. All I done then was mine, and I did very well.

After a few weeks I was doing very well. The Dearth brothers had been called up. They were window cleaners and had several shops, and I got some of their work, and the money was mine. I had to give my mother more money as I was earning more money than Dad. I bought some new clothes, flannel trousers with twenty six inch bottoms, a sports coat, a green polka dot scarf and a green soft Trilby hat. One thing with cleaning windows was you got your money that day.

But it was now 1940, and the war was not going very well for us. We had had a few air raids here but not much damage. Sometimes at home you would hear machine guns being fired above the clouds. The British and French were retreating and things were looking very bad. May 30th started the return of the British Army from Dunkirk. They were rescued by ships of all sorts and sizes, right under the German guns, and now we were awaiting the German invasion. The Prime Minister Mr Churchill gave a speech over the radio and asked all men to join the LDV and help to fight the invader. The LDV was later called The Rome Guard. I joined with Dad, and after a week we got rifles, and we were taught how to use them. Every time the siren went we had to run up to the Church corner and block the road with a hurdle, that was all we had. Sometimes after about half an hour the all clear would go, then it was back to bed, then it might go again and out you go again.

I carried on with the window cleaning, and things were going OK for me. I bought a new bike, it was a Hopper, they were very good bikes. Then Grandmother and Grandfather went on holiday, it was the first time they had ever gone away. They stayed at Epsom, at Grandfather’s brother Edgar's. While she was there she died of a heart attack. The body was brought back to Rendlesham Road. I remember opening the front door, and there was the coffin. I stood alone by the coffin, and I knew that I had lost someone who was always there when I needed her. She had been my Father and Mother and Grandmother all in one, she had always been there when I needed her. On the day of her funeral every house in the road had drawn their curtains. All the neighbours stood along the pavement, and as the coffin passed the men they all took off their hats. She was a much loved lady, she was buried in the same grave as my Father.

After Grandmother's death, Grandfather lived on his own, but he could not manage very well. Mrs Meaking from across the road went over to help him, but Aunt Eva did not like that idea. She got him to move to her bungalow with her, but he did not stay long, she got fed up with him. Then he moved in with Aunt Olive at 5 Allenby Road. He lived in the front room, the window was high up which meant he couldn't see out, so he just used to sit there all day on his own. If the weather was nice he would walk to the corner of London Road, sit on the seat and watch the traffic go by. He was a very lonely old man, he died in the Ipswich Hospital. He was buried with my Father and Grandmother in the same grave.

One Wednesday morning in February, I was cleaning the windows of some offices on the corner of Museum Street opposite Elm Street when a lady came by and as she passed she said "A young man like you should be in the Army". I wrung my wash leather out and up Museum Street I marched, along to the Army recruiting office at Barrack Corner. I opened the door and went inside, there was some black iron stairs, on the wall was an arrow pointing up and the word ARMY. So up I went, at the top of the stairs there was a sign on the door saying KNOCK AND WAIT. I did and a deep voice said "Enter", I did, there were four men sitting around a table. One said "What can we do for you lad?". “I want to join the Army please" I replied. “Sit down, full name”, I told him, “Next of kin, mother, date of birth?”. He looked up at me "What branch of the service?" I said "Infantry". He then read out a list of regiments and the last one was the Queen's Royal Regiment. "That's the one” I said, "Good regiment" he replied, "Are you English?' "Yes" I said. "Be here at ten tomorrow for your medical, sign here" I signed and left. When I got outside I realised what I had done, then I made my way back to Museum Street and picked up the cart and made my way to the Rope Walk Then I went and told Mrs Sadd what I had done, "Why, why, why?” she said. "Well I will have to do the shops myself”, then she gave me three pounds, kissed me and hugged me, "Good luck young Fred" she said. I then got on my bike and started off for home, all the way home I kept thinking what I had done, I seemed to be in a daze. Then I was home. I went indoors and sat down, "What's wrong with you?" I remember Mother saying. "I have joined the Army", "You can't, you’re not old enough", "I have to see the doctor in the morning". She sat down head in her hands "Why did you have to do that?", then she said "Well, if that's what you want". When Dad came in she told him the news, "Well" he said "You will be the first one in the village to volunteer, what are you going in?” “Queens royal regiment, the mutton lancers" he said "You'll be alright".

The next morning I was up early, got my bike out and off to Ipswich for my medical, I left my bike outside the recruiting office and went inside. "Name" the man said "Harvey" I entered the room where the voice came from, there were two men standing and one sitting on a desk. "Strip off'. I took all my clothes off, he examined me all over said something to the other man who wrote in a book. He said "Get dressed and wait outside". I got dressed quickly and was soon out of the door. I did not have to wait long, along came the man who was at the desk, "Report at this office tomorrow morning and you will get your details" he said. The next morning being Friday I was up early, and off on the bike to Norwich Road. I soon found it, it was the house where Mr Glanfield lived. He had been one of the teachers at Bramford Road school. I knocked on the door and a man came out, "Name?" he said. "Harvey”. “Take a seat". I just sat down when a voice shouted out "HARVEY!", I got up and opened the door, an Army officer sat at a desk, “Sit!". I sat. "You are being posted to the Queen's Royal Regiment, your train leaves Ipswich station 8.35am for Liverpool Street and the 2.45 from Paddington for Teighnmouth, South Devon. If you are in any doubt report to the R.T.O. on the station. Stand up and take the Bible in your left hand, raise your right hand and repeat after me", he went on about serving my country, and the King, when he finished he said 'Here are your rail warrants, and the King's shilling", and he gave me a shilling. He walked to the door, opened it and said "Good luck!”. I walked down the path to the pavement, got on my bike, then I started to think ‘I am a soldier. Now I may never come back here anymore’, then I thought I had better call round the shops. The first stop was John Philips ladies clothes shop Westgate Street. I put the bike against the kerb and went inside the shop. I saw the manageress, I said "I won’t be round anymore, I have joined the Army and I go tomorrow". She called the girls, "Fred won’t be calling on us for a while, he has joined the Army and I'm sure you would like to say goodbye and wish him well" then she put her arms on my shoulders and kissed me and said "Goodbye Fred". Then the manageress took my hand and gave me a one pound note, I said "Thank you very much" and left. My next stop was Salesburys in Carr Street, they sold handbags and things like that. It was a small shop. Two girls and a manageress, she gave me a ten shilling note. Then to Bernies ladies shop on the corner of Upper Brooke Street. It was a very posh shop and I got a ten shilling note, then I called at the Wagon and Horses public house and had a free pint. Then I called at the Salutation in Tacket Street, The Bull in Fore Street, The Tankard and The Globe in Bedford Street, then I began to feel a bit woozy. I made my way home.

I told my mother what happened, she did not think I would be going so soon. I had never been to London. I had heard of the underground railway. She said "When the train gets to Liverpool Street it can't go any further, then you get off and get the underground which will take you to Paddington".

Saturday morning I was up early, there was no buses that time in the morning. The first bus was about ten, so unless I could get a lift off someone going to Ipswich, which was very unlikely it meant a very long walk. My things were all packed, I had breakfast, shook hands with Dad, kissed my mother goodbye and I started off down the road. I was going down the hill at Akenham when I heard a car coming, he pulled up beside me. "Where are you going" he said "Ipswich station”. “I'm going to Cocksedges Wherstead Road. I can go by the station” he said, so I got in the car and we got there in plenty of time. When I got on the platform it was crowded mostly with servicemen and women. My worry was how do I get to Paddington. I had a funny feeling in my tummy, I began to feel I would never find it. Then the train came in and there was one mad rush to get a seat. I got on. There were no seats left so I stood in the corridor with lots of others all packed tight together. Next to me stood two soldiers, after a while we got talking. I told them where I was going and one of them said they were going to Bristol and I would be getting the same train as them, they would be changing trains at Taunton, and I would be going on. "Keep close to us" he said. After that I felt a lot better but I don't think I could have found the way to Paddington on my own.

At Paddington they took me into the Y.M.C.A. and there I had some sausage and mash and a mug of tea, then it was time to go on the platform as there would be a rush for seats. I had never seen so many trains in my life and the noise and whistles from the engines, I will never forget that day.

As the train left the station, Ack Ack guns could be seen. Their barrels pointing to the sky. In a park I could see searchlight camps, and overhead the sky seemed full of barrage balloons. Soon the train was speeding through the countryside. And I started to think ‘Four days ago I walked up Museum Street to join the Army and now I have, for the first time in my life, travelled on a train to London, and my first time on the underground railway. And now here I am travelling on the Great Western Railway to South Devon, a place I had never heard of’. After what seemed like hours the train started to slow down, my friends got up and said "This is where we get off". They started to get their kit on , “Yours is the next stop”. They shook my hand and said "All the best" and got off the train. Then we were off again, I must have dozed off as I heard a voice calling to me in what seemed a strange accent "Teighnmouth, Teighnmouth. The train was going very slow, I began to get my things together and made for the door. The train stopped and I got out on to the platform. I stood there for a few moments, then I followed the other people, gave my warrant to the collector, and walked out into the road. Then I stopped, turned round and there was another young lad behind me "Do you know where the Army is?" I said, 'That’s what I want" he said. "I am going in the Queens" I said "So am I" he said. "My name is George Gleed from Hayes in Middlesex". "I am Fred Harvey from Ipswich, Suffolk. From then on George and I became very good pals.

When we got to the bottom of the hill we had to turn right along another road. We could see the sea then we saw a flag. It was a big house, the sentry on the door made us halt, then called for the Guard Commander. "Follow me" he said, we did then he took us into a room and told us to wait. He returned with a Sergeant. He took our papers and asked us our names. "You are the last of the intake", then he called “Corporal” and a corporal came. "Take these two to Galway house, fix them up for the night, we will see to them in the morning". "Follow me" said Corporal, so off we went up another big hill At the top was what looked liked like a park. In the grounds was this very big house. He took us to a shed and gave us two bags and a small one. "These are your palliasses, fill them up with this straw, that’s your bed". Then he gave us three blankets, he said "You will have to sleep in the bathroom tonight, you'll get fixed up in the morning. Had any grub?" we said "No". "Come with me" he said. Down the hill we marched, down by the sea front was a big building, it said Spar Pavilion. We went round the back. "Charlie" the corporal shouts, out comes this bloke Charlie, an oldish looking man with first war ribbons on his jacket, and a fag hanging out of his mouth. "Got any grub?" said the corporal, 'Well it ain’t grub is it Charlie it's shit”. “Come with me” says Charlie. He gave us a plate. He went up to a big copper put his hand in and pulled out a handful of potatoes and plonked them on my plate, then the same to George. The potatoes had their skins on, and it looked like mud as well. Then he went to the next copper and pulled out a handful of soggy cabbage. Then he cut off a lump of corned beef. He said "Better have a drink” he gave us a mug each, it tasted like thick cardboard. The corporal said “You'll be all right” . "Right" said the corporal, “back to Galway house”, up the hill we went again and back to our bathroom. "You can go out if you want but be outside at 6.30 on parade for breakfast. See you in the morning" he said then he left us to our thoughts,. "Let's go out and see what’s about" said George, so down the hill we went again. This time we walked along the sea front. On the corner of a road stood a public house. We went inside, there were only four old looking men in the room. "Two pints of beer please" said George, "No beer me dear, only cider, what e want, rough or sweet?". I didn't know what to say so we had sweet, it tasted very nice. We drank up then got two more, one of the men in the corner got up and came to our table. "You be soldier boys" he said "you be in Gallway House, oh watch ‘er me dear, she haunt Gallway, she do". We finished our drink "You have a drink with I" said the old man and he ordered two pints of rough, "Do e good" he said. Then the old man's friends came over and they in turn bought us rough. George got up to go to the toilet and his legs gave way and he fell down. That made the old men laugh. I got up and it felt as if I was walking on nothing. What happened I don't remember but the old men took us back to Gallway house. We must have slept with our clothes on.

We woke up with the sound of someone shouting "Outside on parade for breakfast". So we somehow got outside and on parade. We had to march down the hill to the Pavilion. Inside the Pavilion we had to get in line and hold up your plate out and you got two ladles of porridge. When you had eaten that you lined up again. Same plate and you got two small pieces of bacon and a fried slice. Then you had to borrow someone's cup so you could have a cup of tea. Then outside on parade and march up the hill. There were about thirty lads like George and me who joined up on that Saturday. Most of them came from the London area, that's how they got there early. They were good lads, a bit wild at times. There was Jack Croty he was very thin, he was nicknamed Pull-through, Bill Jones, Ernie Lyord, Smudger Smith, Jacky Cartwright, Bill Butcher, he made his own fags they were like matchsticks. I can see them all in my mind sometimes, they were all very good pals. And so we marched up the hill. When we got to Gallway house, before he let us fall out the Sergeant shouted out "Get your room tidy it's like a tip in there. Gerry could come along at any time, we don't want him to find an untidy room do we!". No one answered him. He repeated what he had said and pointed to his three stripes, "What are these?" he said. We all said “Sergeant stripes”. "Right, so when I say we don't want Gerry to find an untidy billet, you say no Sergeant, WHAT DO YOU SAY!!?" we all shouted out "No Sergeant”. We had just got into the room when in popped the sergeant shouting. "Outside on parade, look lively, you are now about to become soldiers and collect your kit”. Off we went down the hill to H.Q. We halted outside a door and got into single file. Then we filed along slowly. As we moved along we were given two shirts, two pairs of everything. The last thing was the kit bag in which we put all our kit. Then it was outside and up the hill again. When we got back, we were told to get dressed like soldiers and get your civvies packed up to send to your Mum, we won't want them anymore.

In the evening George and I went into Teighnmouth. We went into the pub and we had a pint of sweet. The old boys were there, they spoke to us, but we didn't stay long. We walked around the town, then we saw a house which said on a board ‘forces welcome’. We went in. There were some of the other lads there. We were given a hymn book We sung the hymn Shall we gather at the river, and When the roll is called up yonder. After that two young ladies came round with slices of bread pudding, which we devoured with ease. After we had eaten our bread pudding, one of the young ladies said there would be a short prayer meeting and we were all invited to stay, but we all went out. We called at the pub on the way back The old boys were still there, and they bought us a drink Then it was back to Gallway House. We were woken up with the cries of "WAKEY WAKEY, RISE AND SHINE!". So we got up from the floor. Folded our three blankets up, folded the palliasse in half and laid our kit out on the bed as shown. Then we went outside in the yard to the tap for a wash and a shave in cold water. Then it was outside on parade for breakfast. Mess tins in your left hand, knife, fork and spoon in the right hand and stepping off with the left foot off we went down the hill. We filed into the dinning hall a mess tin in each hand. As we filed along we were given a ladle full of watery porridge in one tin, a slice of bread, a slice of bacon and a fried egg in the other tin. When you had eaten your porridge you held your mess tin out and a cup of tea was poured into it. After you had eaten, you filed out, on the way out you put your mess tin in a bucket of water, that was how you washed it. Then it was fall in and up the hill again. When we got back it was clean the room up. The next parade was to see the M.O.. Roll your right sleeve up, we already had our jackets off, there we were given two inoculations. Then roll the left sleeve up and we were given a vaccination. When everyone had been done, outside, and up the hill. When we got back we were told 48 hours "excused duty and rest. Those two days were spent mainly in bed, we all felt very ill. It felt like a bad attack of the flu.

The 48 hours passed, we felt a little better. Arms a bit stiff, we marched to breakfast and back, then down again. We marched up and down the prom doing different drills. In the afternoon it was rifle drill. Your arms and legs felt as if they had been beaten as they ached so much. Then it was unarmed combat. You had to attack the instructor and you would finish up with a bump on the hard ground and you would ache all over again. We went on the range, firing our rifles, bayonet drill at night, each section took it in turn to patrol along the shore over the rocks. You would be out until daybreak Then it was breakfast and on parade and more drill, on the go even on Sunday. It was church parade. Then outside on parade, arms drill, lectures on the Bren gun and the Lewis gun, gas attacks, gas drill. Then we moved after three weeks to a camp at Barnstaple. We had bunks to sleep on and a mattress. Much better, more training. Then move this time to Plymouth. German planes came nearly every night and dropped bombs, a lot of people were killed in Plymouth. From there we moved to a place called Boltop. Boltop was a huge stretch of flat ground. It was an emergency ground for Spitfires the fighter planes, the RAF had a wireless station out in the middle in a covered lorry.

One day sixteen spitfires crashed. They had been out on patrol in the channel, and it came on foggy and they could not get to Exeter their home base. They had to keep flying around until they ran out of fuel then they crashed. We had to keep firing flares at them, but they could not see them. Most of them crashed in the sea, one went into the side of a cliff and his tail was sticking out.

One day we were going in to the dinning hut for dinner, when a German Heinkel bomber came over. He came down and taxied across the landing field and then took off again, and not a shot was fired at him. Our next move was to Minehead in Somerset. We had a new C.S.M. posted to us, he had his girlfriend or wife I don't know which but she stayed at the farm house near our camp. The farmer by the name of Jed Prout wanted some help on the farm. As I came from Suffolk the C.S.M. detailed me, I had to report at the farm at 7am. One day he took me in his broken down old lorry to a place called Porlock, he bought some cows from another farmer. I had to drive them back to Hatchet, that was the name of the place where the farm was. On the way home I was driving these cows slowly along the road, when there he was, he had put his lorry right across the road. He had opened the gate to the meadow. There he was shouting "Get ‘er in ‘ere me dear get ‘er in ‘ere". He had sold them and they now belonged to the owner of the meadow. He paid me sixpence a day. I got my meals if I was lucky. When he had a row with his wife no one got any food. There was another old man on the farm, he slept with the horses. I don't think he ever had a wash, only time he got wet was when it rained. There was also the maid, a simple girl called Polly. If I was working out in a field he would send Polly to me with a bottle of cider and a lump of home made bread. Sometimes I got my tea, then he would give me sixpence. He would then get the cards out and would want to play halfpenny nap. Sometimes he got his money back.

Then it had to end and we had to move to Newton Abbot and we got seven days leave. The train left Newton Abbot about eleven. It was a long journey. When we got to Paddington Station, people were coming up from the underground where they had been sleeping all night. Some people were still asleep. Children were crying, it was a terrible sight. It took a long time to get to Liverpool Street station. When I got there it was a long wait for the train to Ipswich. It was evening before I arrived at Ipswich Station. And being late there was no buses, so it meant the long walk home to Henley. As I was going by the Dales there was a man standing in his garden. He said "How far do you have to go?" I told him, "Wait here" he said then went inside and came out holding a pint glass of beer. I thanked him and continued on my way.

Soon the houses of Henley came into view, and I was soon going up the path to the back door. I opened the door, my mother was standing by the table. "Boy!" she shouted. I took off my pack and the rest of my stuff. I gave her my ration card and ration money. I had seven days leave, one had almost gone already, I had five left. The seventh would be spent going back. There was not much to do at Henley. I biked into town every day, walked around and went to the pictures. My leave soon passed, and in a way I was glad to be going back.

The morning after I got back, we were on parade. Then the order was, if your name is called, fall out on the right. Names were called then I heard "Gleed" that was George and still not me. Then he finished the list. "Get your kit packed" he said “You lot are going to the Thirteenth Battalion Queen's. The remainder can start packing, you will be away in the morning. You are going to take a trip to Ireland. In less than two hours they were gone. The next morning, after breakfast we were out on parade. They gave us our rail warrants. We were given instructions and were taken to the station. We had to get the troop train for Stranrarr in Scotland at Euston Station. Then the boat from Stranrarr to Larne. From Larne to Belfast and from Belfast to Down Patrick We got to Stranrarr in the early hours of the morning. We boarded the boat. It must have been about midday when we arrived at Belfast. As you went through the ticket barrier we were given a cup of tea from some ladies. By the time we got sorted we found out that we had missed the last train. So we walked into Belfast and found the Y.M.C.A. and booked a bed for the night. The next morning up for breakfast, then down to the station. We called at the rail transport office and asked the way to Ballykindler. We were told that the rail only went as far as Down Patrick, and if no one picked you up it was a long walk. We arrived at Down Patrick, and we walked all the way, along all the lanes. Then we reached the camp right under the mountains. We went to the Guard room, the Corporal took us to a hut. Dump your kit, get three biscuits and three blankets from the stores, we did. Then we went to the dining hall for our tea. You will be sorted out in the morning. Sandy's canteen is open all day so you can get all you want there, and there's the pictures with a different film every night. We went to the pictures, it was a cowboy film about Custer and Richard Dix was the star.

Next morning on parade we were given our jobs. I was told to report to the Sergeant cook at the officers mess. Off I went, I found the cook a nice old boy. He said "Have you ever done any stoking?" I said "No" "You'll soon get the hang of it. The other side of the parade ground you can see a big shed. Well there's four big boilers, all you have to do is keep them going night and day. And make sure that the fires are alight in the morning. The girls will be here in the morning to cook the breakfast, that's all you have to do. Get your kit, you kip in here with me, then you can start your job". So I moved in, he introduced me to the girls in the kitchen. Then I went to see the boilers. They were great big things with knobs and switches and levers. I hadn't a clue what to do, so I just shovelled some coal on them hoping that would keep them alight. They did all but one night, they went out and the officers had no hot water to wash with. I was lucky, there was an Irishman who worked in the camp and he came and saw me. He had worked on the boilers and knew all the snags and how to work things out. He said “If you get in a fix give me a shout", he soon got things going again.

One night we had a E.N.S.A. concert party come to the camp. They put on a show. One of the stars was Bebe Daniels, she was a film star and was married to Ben Lyon the American film star. They had a program on the wireless. After the show they all went into the Officers mess. "Before we go to bed" Cookie says "When they have all gone, we will go and see what there is left". It wasn't long before he was shaking me. When we got to the Officers mess there was bottles and glasses everywhere. There was Whiskey, Rum and Brandy everywhere. We were filling up bottles and glasses and drinking it as well. I soon began to feel a bit silly, that’s all I remember. Cookie told me later, that when the A.T.S. Sergeant came on duty with the girls they found me asleep on the settee. He said the A.T.S. Sergeant detailed three girls to carry me to the bathroom. They then took off my clothes and put me in a bath of cold water. "Boy" he said "We were lucky to get away with that”. The Irishman who helped out when the fires went out came round and he was rewarded with a few bottles.

The stay in Ireland did not last long and we were soon off back to England to a place in Lancashire called Ramsbottom, another place I had never heard of. We were met at Manchester Station by a Corporal and driver with a truck We were taken to an old mill just outside Ramsbottom. There were streets with houses all around us. There we met up with some of the lads who had been at Teighnmouth, one of them was Jacky Cartwright who I knew. He said there was not a lot to do in Ramsbottom. He had a girlfriend and she had a mate. So he said "come with me, there’s a cinema which changes the films twice a week and there’s also the pubs". So that evening I went out with him. I met his girlfriend Lucy and I went with her friend, a girl called Winnie Bullock. She was a tall girl with hair which went over one eye. Whenever we were free to go out we always went together.

Every day we were out training, mostly route marches in bare feet to harden up our feet. We always mounted guard in the street, it was always a stick orderly guard, that means seven men go on parade to mount guard. The smartest one on parade gets off the guard and is company runner the next day. All the street used to watch the guard mounting and bets were made among the local people who would be made stick orderly. Being on guard wasn't so bad. People would bring you out supper, cups of tea and give you cigarettes.

Then one morning it was outside on parade. We fell in, fall out to the left when your name was called. Then we were marched off to the M.O. for inoculations. After that get your kit packed and hand your blankets in at the store. We collected our ration cards and rail warrants for fourteen days leave. Then we climbed aboard the truck to take us to the station. My mate Jacky said he would come later as he wanted to see Lucy and tell her the news. It was a long journey to London, and the trains had stopped running when we got there. The underground station platform was full of people trying to sleep and the children were crying, it was very sad. Soon it was morning and the trains were running and I was soon at Liverpool Street Station. Another long wait for the train to Ipswich. When I did arrive at Ipswich the buses had stopped running so it meant the long walk to Henley.

My mother looked very sad when I told her I was on embarkation leave, but she said she knew it would come. There was nothing to do at Henley. So most days I went into Ipswich, sometimes I met Audrey Rae and we went to the pictures. Some evenings I went to the Claydon Greyhound pub. On my last night of leave, Mother and Dad came with me. There were several people in there. Just before we went home Annie Quinton the landlady called me to the bar. I went up, she put her hand up and asked for silence. She said "Young Fred is going away, we wish him luck and a safe return to us". In her hand she had a length of string, it was threaded through a hole in a threepenny bit. She put it over my head so it hung round my neck. "I want you to wear this at all times, and I want you to bring it back when you come back home”. Then she kissed me and hugged me tight, 'God bless you, young Fred" she said. I looked at my mother, she had tears in her eyes. Then Annie called time and we got on our bicycles and rode home, in the dark with no lights. There were searchlights sweeping the skies.

In the morning mother called me early, and I caught the bus from Coddenham. I felt very nervous and frightened. I wondered if I would ever see Henley again. I got off the bus at Ipswich and walked to the station and soon I was off to London again. In London I soon found my way to Euston station. Most of the lads I knew were there. Jack was there with his mother and sister. And then we were off, his sister and mother were crying as were lots of other people on the platform. When we got to Ramsbottom we called in the pub for a drink. Lucy and Winnie were waiting in case we called in. We told them if we were able we would see them the next night. Next day we were getting ready to go, make your will out, next of kin, then we were allowed out but had to sign in at the guard room at 22 00 hours, we were going next day. We went out and met the two girls, then they came back with us. Jack had the idea that we would sign in, then nip round the back over the assault course and take Lucy and Winnie home. It was getting dark when we signed in. All went well, we reached the assault course, then to cross the stream, there were stones to jump on to get across. He picked Lucy up and got across. I picked Winnie up and got almost to the other side. Somehow I dropped her, she got her feet wet and I fell back and sat in it and got soaked, so we never took them home after all.

It didn't seem long before it was wakey wakey. I had to get dressed and my trousers were still wet. Then it was breakfast, then outside for roll call. We climbed on to the truck and away to the station. The train was already in and we got settled down, first stop was Liverpool. We had to stay in our seats until we were told to get out. While we sat there some more Queen's came by. Among them was my pal George Gleed. They were now joining us, I felt a lot better. We formed up the station with the others, and marched down the road to the docks. Our draft officer had to go aboard first to find our deck, and our duties while aboard ship. He came back and we followed him along the gang plank. Once on board we had to go down lots of stairs. Then we had to pick up a hammock and a blanket. Then you filed along the side of a long table. You stopped where there was a hook above your head and that was where you slept and ate until you got off the boat. As we were a small draft we got picked to find crews for the Ack Ack guns. She had six Oerlikon guns, two men to a gun. George and me had one at the back of the second funnel. Then we had to report to the guns officer, he told us how to handle the gun. In the evening we sailed, in the morning we stopped and there were ships of all sizes around us. We had instructions on the gun. Then we just walked around the ship, she was a New Zealand ship, her name was RANGITIKI.

We were looking out at all the other ships. Then lights flashed from each ship. Then there was a ship sounding and each ship answered in turn, then they all seemed to move off as one. We were shown where we would sleep, so as to be near the gun and it would be two on, four off. We were given a ticket for the canteen so that we never had to line up. We had a few submarine alarms. When that happened the escorting Destroyers flew a black pennant on their mast. The troops all had to go down to their decks and stay there. We had warnings of aircraft, and heard gunfire coming from the front of the convoy, apart from that it was a peaceful trip. We pulled into Freetown and stayed for about three days I think. The native children would swim out to the ship and ask for Glasgow tanners. You threw a sixpence into the sea and they would dive down into the sea and come up with your sixpence in their mouth. Then we were off again, we had the odd alarm, but that was all. Then one morning I was lying on the floor on my blanket when I heard a lady singing. I got up and opened the door and I saw huge white buildings. As we moved along slowly, this lady dressed all in white was singing through a megaphone. The troops waved and sang with her, it was a sight I shall never forget.

We were looking out at all the other ships. Then lights flashed from each ship. Then there was a ship sounding and each ship answered in turn, then they all seemed to move off as one. We were shown where we would sleep, so as to be near the gun and it would be two on, four off. We were given a ticket for the canteen so that we never had to line up. We had a few submarine alarms. When that happened the escorting Destroyers flew a black pennant on their mast. The troops all had to go down to their decks and stay there. We had warnings of aircraft, and heard gunfire coming from the front of the convoy, apart from that it was a peaceful trip. We pulled into Freetown and stayed for about three days I think. The native children would swim out to the ship and ask for Glasgow tanners. You threw a sixpence into the sea and they would dive down into the sea and come up with your sixpence in their mouth. Then we were off again, we had the odd alarm, but that was all. Then one morning I was lying on the floor on my blanket when I heard a lady singing. I got up and opened the door and I saw huge white buildings. As we moved along slowly, this lady dressed all in white was singing through a megaphone. The troops waved and sang with her, it was a sight I shall never forget.

When the ship stopped, Lt Patterson came along and told us to go below and draw our rifles from the store, get all our kit and parade on deck. We were only a small draft and we were first to leave the ship. Lorries were waiting. After a while out in the country we came to a big camp, it was called Clairwood. Just down the road was a horse racing stadium. We were taken into a brick building with no windows or doors, no beds or bunks. Wherever you dropped your kit bag that was your bedspace. We had to go over to the store and get a straw palliasse. There was not a lot of straw in it but it was better than laying on bare concrete.

Every morning we marched to the race track and lined up at the starting gate, and ran round the track, then back to camp for breakfast. After breakfast, we had a talk about the desert, or German or Italian armour and other weapons. Most mornings we went out onto the range. We had to line up spaced well apart. Ahead of us there were three rows of dummies dressed like German soldiers. There were three rows of them, then further back were stuffed bags. The idea was when the officer shouted “Charge” you ran towards the first targets. Before you got there, there was a trench. You jumped in and fired five rounds at your target. When the officer fired his revolver you got up and repeated the same thing again. Then you reloaded your rifle, when he fired his revolver off you went again. By now you are getting a bit weary. You fix bayonets, and he fires his revolver and off you run screaming your head off. You reach the stuffed bags, you have got just enough energy to stick it in the bag. All the time you are doing this the other N.C.Os have got watches and are timing you at each target.

When you get back they say “After dinner you can go out”. The nearest place to go is Durban. There are no buses, there are taxis and a railway station, but it's a seven mile walk. Four of us went to Durban. We got the train, it's a lovely place Durban is if you have got the money. We walked around the town, we went to the cinema. During the interval they came round with a cup of tea. Everywhere you looked there were notice boards saying Europeans only. If you walked along the path and a black man or woman did not get off the path to let you pass, you could report them and they would get flogged. If you stood at the bus stop, they were not allowed to stand on the same side as you. They were allowed four seats on the top deck of the bus, but if those seats were already taken they were not allowed on the bus. We were not there many days and we were off.

This time the name of the ship was the Sterling Castle. She had guns but they had their own crews. After we got settled in our deck, we went up top and as we moved off there was the lady in white again singing There'll always be an England. I wondered if I would ever see England again. We sailed around Cape Horn. I had read about it at school, but I never thought I would ever sail round it. I do not remember how long it took us but we were having tea and the ship slowed down. We were entering the Suez Canal. Later the ship stopped and we were told this was as far as we go. The name of the place was Port Tewfick. We had to stay on our deck until the others got off. They were all morning getting off. Then we collected our rifles and kit and marched down the gang plank. We marched through the dock gates and waiting there were four lorries. We were ordered to halt. Then this Sergeant came up with a piece of paper in his hand. "Fall out to the right when your name is called" he shouted. The first name was J. Pope. There were several more lads I knew, G. Gleed that was my old mate, then more names, then I heard 392 Harvey. F. I felt a lot happier.

Davies, Tommy Trustler, Blakey he was there- Then the sergeant came in, his name was Tom Best, he gave me all the details about what was happening. Then he had to see the others. The next day on parade, full kit, total weight on your back was 70 lb. The camp was beside a big dam. We had to do a lot of river crossing. Before anyone entered the water hand grenades were thrown in to scare any crocodiles that may be around.

We had Christmas dinner at Jahansi. We finished training the day before. The next day, Boxing day we were off on the train. I didn't see George all that much, he was with a sergeant Sharman in another part of the dam, but we got together with the column on Christmas day 1943. Before we left Jahansi, we had a visit from Lord Louis Mountbatten. He was now the Supreme Commander of South east Asia. He hadn't been in India long as he had been in England. As soon he arrived he called out “Gather round”. He told us what life was like back in England. Then he said "You say you are the forgotten army, you are not forgotten, no one has heard of you, but they will from now on. We are not retreating anymore. We are going forward from now on and we will finish the job".